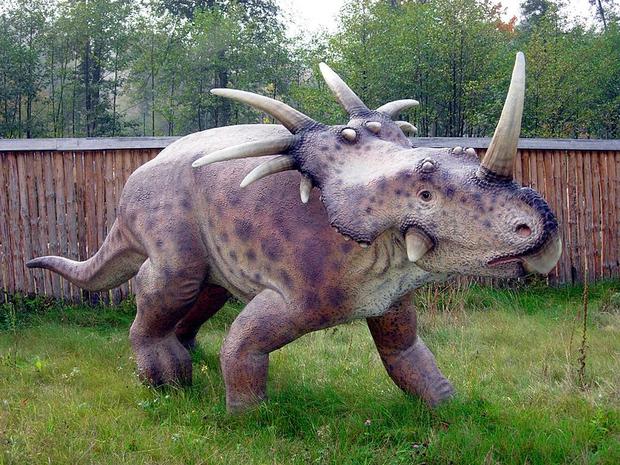

10 Interesting Facts About Styracosaurus

1. INDIVIDUALS HAD SLIGHTLY DIFFERENT FRILL SPIKES.

Also known as “parietal horns,” the relative size of these pointy structures varied noticeably between Styracosaurus specimens.

2. STYRACOSAURUS PROBABLY USED A DIFFERENT FIGHTING STYLE THAN TRICERATOPSDID.

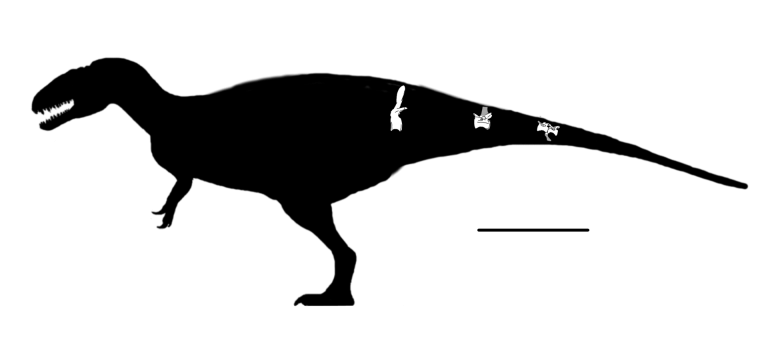

In a 2009 effort to shed some light on dinosaurian combat, a paleontological team compared several skulls from Centrosaurus (pictured on the left) and the famed Triceratops. Scars consistent with locked-horn showdowns are, it turns out, quite common on Triceratops heads, but relatively rare in Centrosaurus remains. Perhaps this is because the latter herbivore—like its close cousin Styracosaurus—lacked formidable horns above its eyes and probably had to find other means of clashing with rivals.

“Possibly Centrosaurus wasn’t using its horns for fighting,” says Dr. Andrew Farke (who helped execute this study), “or, if it was fighting, it was concentrating its energies on parts away from the skull, like maybe flank-butting or something like that.”

3. STYRACOSAURUS APPEARS IN THE WEIRDEST WESTERN EVER MADE.

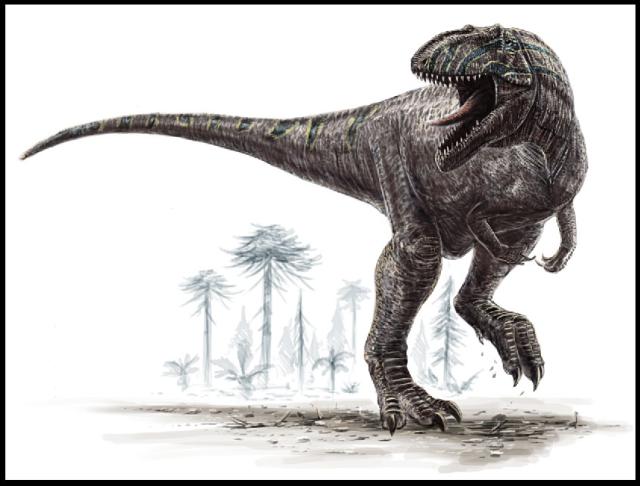

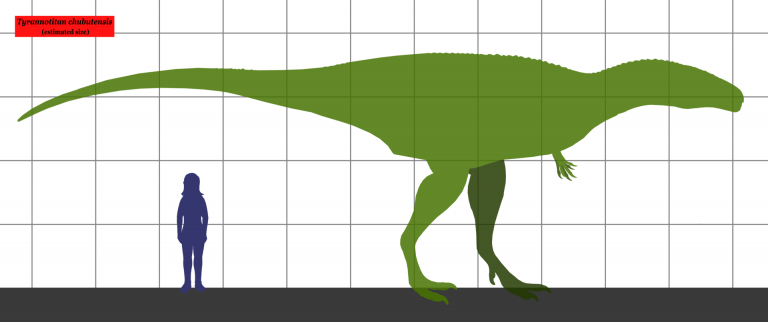

Cowboys wrangle stop-motion dinosaurs in Ray Harryhausen’s epic creature feature The Valley of Gwangi (1969). At one point, predatory “Gwangi” (whose design was loosely based on T. rex and Allosaurus) takes down an enraged Styracosauruswith some help from a spear-toting horseman.

4. …BUT WAS CUT FROM KING KONG (1933).

Though animator Willis O’Brien had shot a thrilling action sequence with his poseable Styracosaurus model, this scene wound up getting scrapped. Fortunately, when the hasty sequel Son of Kong (1933) was churned out less than a year later, “Obie’s” Styracosaurus finally secured some screen time.

5. SCIENTISTS HAVE BEEN DIVVYING UP STYRACOSAURUS.

What’s in a (scientific) name? Clarity, for starters. Once upon a time, Styracosaurus included three recognized species: S. albertensis, S. parksi, and S. ovatus. In 2007, though this dino got a classification makeover, with S. albertensis and S. parksibeing merged into a single species thanks to their virtually indistinguishable anatomy. Meanwhile, S. ovatus was placed within an entirely new genus and is now called Rubeosaurus ovatus.

6. STYRACOSAURUS’ NOSE HORN WAS SHORTER THAN MOST PEOPLE THINK.

When studying fossils for a living, incomplete specimens can be the bane of your existence, and Styracosaurus’ distinctive nose horn falls into this category: Most of what we know about this nasal apparatus is based on fragmentary fossils. Though it’s traditionally been assumed to have been around 20 inches long, a closer examination reveals that the horn was around half that length (and possibly blunt-tipped).

7. SOME HAVE SAID THAT STYRACOSAURUS HAD ABSURDLY-HUGE JAW MUSCLES.

The flashy frills of ceratopsians (horned dinos like Styracosaurus and Triceratops) have inspired much debate over the years. Paleontologists Richard Swann Lull and John McLoughlin independently proposed a radical explanation about their function: Perhaps these huge, bony structures were nothing but attachment anchors for the creatures’ (presumably gigantic) jaw muscles. This idea holds that the frill was buried in flesh and bound to the dinosaurs’ necks and shoulders.

Today, most experts currently believe these frills were predominantly display-oriented features. However, there’s no doubt that ceratopsians packed some powerful bites; for more info, check out this entertaining write-up.

8. STYRACOSAURUS BELONGED TO A SUPER-ORNAMENTED SUBFAMILY.

The centrosaurinae is a group of ceratopsians whose members lacked large horns above their eyes, had pronounced nose horns instead, and rocked short, well-decorated frills.

9. CRUSHED SKULLS DISTORTED MANY EARLY STYRACOSAURUSILLUSTRATIONS.

Fossilization can be a cruel mistress. One of the world’s most complete Styracosaurus skulls contains a crucial flaw: Its frill has been artificially bent by the elements. This specimen was unearthed in the 1910s and helped scientists understand what the strange animal looked like. Several academic paintings and sketches would be based upon this magnificent fossil. But, unfortunately, geological forces had, over time, unnaturally crushed the dinosaur’s frill, forcing it downward and making the apparatus appear as though it jetted out directly behind Styracosaurus’ skull. Thanks to a second skull that turned up later, we now know that this frill was held at a more upwards angle.

10. IT’S NAMED AFTER ANCIENT GREEK SPEAR SHAFTS.

The steel spike at the end of a spear was known as a styrax in classical Greece, this term wound up inspiring the first part of Styracosaurus’ genus name.

Source: www.mentalfloss.com