On Isolated Madagascar, Even Prehistoric Evolution Was Unique

More than 70 million years ago, the world’s fourth-largest island separated from Gondwana.

It has remained a loner ever since.

Situated off Africa’s southeastern coast, Madagascar’s continued geographical isolation means that today, about 80 percent of its wildlife — which includes zoologically primitive primates and hedgehog-like insectivores — is found nowhere else in the world.

That same isolation also greatly affected the evolution of Madagascar’s Cretaceous Period dinosaurs, bizarre creatures that included Masiakasaurus knopfleri, a predatory theropod or meat-eater that stood just 30 inches high, sported strange-looking, forward-pointing teeth at the front of its mouth, and was discovered by a team led by David W. Krause, senior curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

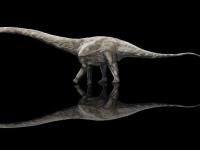

Equally unusual was Majungasaurus crenatissimus, a 4,400-pound, cannibalistic predator with a taste for sauropod flesh and “arms” — forelegs too small to have been useful for feeding or hunting.

Perhaps such limbs were a feather-covered factor in attracting a mate, says Joe Sertich, curator of dinosaurs at DMNS. He discovered the fossilized Majungasaurus skull and neck bones housed at the museum as part of its Madagascar Paleontology Project and displayed in the special exhibition “Ultimate Dinosaurs.”

Other oddities include rahonavis, the smallest Cretaceous Period dinosaur found thus far on Madagascar. Although this theropod probably had feathers and might have been capable of flight, rahonavis wasn’t a direct relative of birds, the living descendants of the dinosaurs. It might, instead, have been a genuine link between small theropod dinosaurs and “true” birds.

And then there’s Simosuchus, a stubby, blunt-snouted, and rather cute (to me, at least) creature that turned out not to be a dinosaur at all, but a land-dwelling, plant-eating crocodilian completely unlike any modern crocodile.