Missouri Dig Site Is Home To At Least 4 Rare Dinosaurs, And There Could Be More

The first tracings of dinosaurs in Missouri were found in the 1940s on the Chronister family's property when they were digging a well. In October, nearly 60 years later, another set of fossils from the same species were uncovered about 50 feet (15 meters) away.

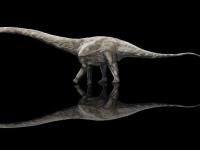

After comparing and matching the tail vertebrates of these discoveries, paleontologists described them as "relatively primitive" duck-billed dinosaurs.

The specimen of the state dinosaur of Missouri, named Parrosaurus missouriensis, was excavated after a years-long process that began in 2017, Chronister site curator Peter Makovicky said. Makovicky is a professor of Earth and environmental sciences at the University of Minnesota.

"Whenever you find a locality in the Midwest or in Eastern North America, where you're getting multiple dinosaur skeletons coming out of one site, it's really a windfall with almost no parallels," he said.

Fossils in Missouri are rare -- the Chronister site, a couple dozen acres of woodland located near Bollinger County in Missouri, is the only place fossils have been found in Missouri, according to Erika Woehlk, a visual materials archivist at the Missouri State Archives. Most dinosaurs in the United States have been found in the West.

"No one thought that there were any dinosaurs in Missouri. It's just unheard of to find dinosaur fossils in this part of the country," said Abigail Kern, office manager for the Sainte Genevieve Museum Learning Center in Missouri.

But this site is rich.

While uncovering the dinosaur, Makovicky and his team found several turtle fossils, which paint a fuller picture of the ancient ecosystem. Paleontologists have also found parts from at least four different dinosaurs, Makovicky said, including a juvenile dinosaur of the same species found in the early 2000s.

The largest block of the dinosaur -- 2,500 pounds (1,134 kilograms) -- was excavated with the help of a crane on October 15. The fossil will make its way to Chicago's Field Museum for preparation and research.

A fossil site decades in the making

The fossils found in the 1940s were sent to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. The site remained stagnant until the 1980s, when renewed interest in the fossils led Missouri paleontologist Bruce Stinchcomb to purchase the property from the Chronisters.

Scientists debated this fossil's genus for decades. In 2018, paleontologists landed on the initial genus, Parrosaurus, coined in 1945. This dinosaur has been reclassified four different times, but Woehlk said reclassification isn't that unusual.

Wet clay at the excavation site, and the pandemic, complicated and prolonged the four-year process, Makovicky said. He's more accustomed to excavating fossils from hard rock, so the team had to work slowly around the softer clay.

With the observations and findings of the site, paleontologists can have a better understanding of the ancient environment -- and assess areas for further research and excavation.

Makovicky said they are still determining the exact age of these fossils and learning more about the distribution of dinosaurs across North America.

"There's just a lot more to learn about these ancient environments and how they relate to our knowledge of ecosystems and evolution," he said.

Sainte Genevieve Museum Learning Center is home to the juvenile specimen, and its laboratory is viewable to the public. Starting in December, museum visitors will be able to watch paleontologists and other scientists prepare the fossils, according to Kern.

Because fossils are hard to come by in the Midwest, Kern hopes these rare discoveries will get children excited about archaeology and geology.

"We're a very small town in rural Missouri so we're just really excited to be able to bring this level of scientific finding to our town and to help push it out to all of the communities and the schools around us," Kern said.

Source: https://edition.cnn.com/