Sinornithosaurus

Sinornithosaurus (derived from a combination of Latin and Greek, meaning ‘Chinese bird-lizard’) is a genus of feathered dromaeosaurid dinosaur from the early Cretaceous Period (early Aptian) of the Yixian Formation in what is now China. It was the fifth non–avian feathered dinosaur genus discovered by 1999. The original specimen was collected from the Sihetun locality of western Liaoning. It was found in the Jianshangou beds of the Yixian Formation, dated to 124.5 million years ago. Additional specimens have been found in the younger Dawangzhangzi bed, dating to around 122 million years ago.

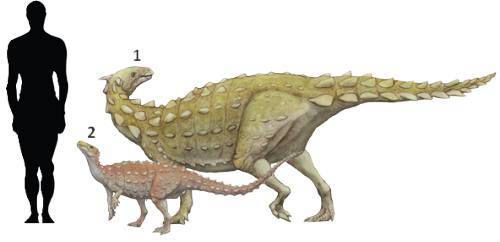

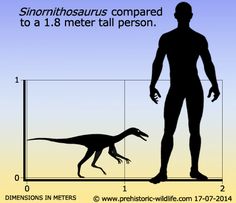

The small predatory dinosaur Sinornithosaurus was a dromaeosaurid-one of a group of agile bipedal runners with large eyes, relatively large brains, and long, narrow snouts equipped with steak-knife teeth. The three fingers on each hand and the four toes of each foot had long, curved, wickedly sharp claws for hooking into prey, with the second toe claw being extra large. As in many other dinosaurs, especially fast-running kinds, the tail was stiffened by overlapping bony rods.

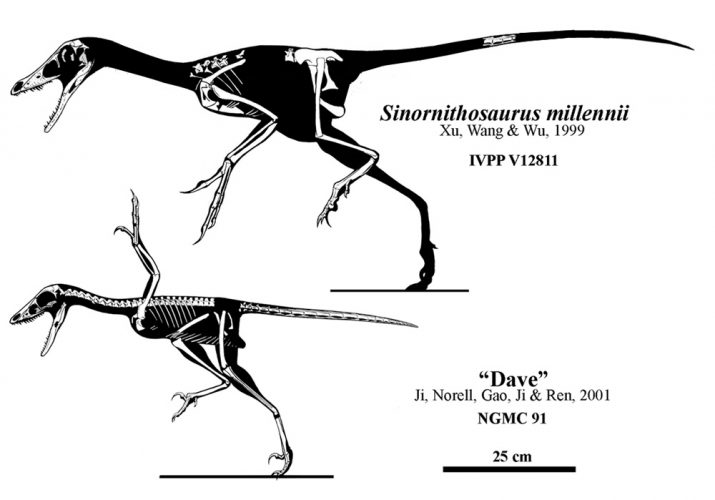

Sinornithosaurus was discovered by Xu Xing, Wang Xiaolin and Wu Xiaochun of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of Beijing. An almost-complete fossil with feather impressions, was recovered from Liaoning Province, China, in the Yixian Formation; the same incredibly rich location where four dinosaurs with feathers were discovered previously, Protarchaeopteryx, Sinosauropteryx, Caudipteryx, and Beipiaosaurus. The holotype specimen is IVPP V12811, in the collection of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, China.

The NGMC 91 specimen is in the collection of the National Geological Museum of China. It was collected in Fanzhangzi quarry, near Lingyuan City, Liaoning Province. This location is part of the Dawangzhangzi fossil beds, which have been dated to about 122 million years ago, during the early Aptian age. A specimen of the fish Lycoptera is also preserved near the foot.

Phylogenetic studies did not support the idea that NGMC 91 was a close relative of S. millenii. In a 2004 analysis, Phil Senter and colleagues found that it was, in fact, more closely related to Microraptor. Subsequent studies, also by Senter, have continued to show support for this finding despite the fact that some data used in the original study was later found to be flawed.