Centrosaurus

Centrosaurus is a genus of herbivorous ceratopsian dinosaurs from the late Cretaceous of Canada. Their remains have been found in the Dinosaur Park Formation, dating from 76.5 to 75.5 million years ago.

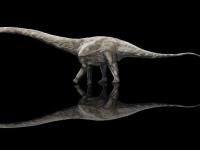

The massive bodies of Centrosaurus were borne by stocky limbs, although at up to 6 m (19.7 ft) they were not particularly large dinosaurs. Like other centrosaurines, Centrosaurus bore single large horns over their noses. These horns curved forwards or backwards depending on the specimen. Skull ornamentation was reduced as animals aged.

Centrosaurus is distinguished by having two large hornlets which hook forwards over the frill. A pair of small upwards directed horns is also found over the eyes. The frills of Centrosaurus were moderately long, with fairly large fenestrae and small hornlets along the outer edges.

Centrosaurus, which moved on all fours, had powerful front limbs that would have enhanced the animal’s speed and agility. A ball-and-socket joint in the neck would also have been useful in defense. it allowed Centrosaurus to turn its head swiftly and bring its sharp horn into play against large predators, such as Tyrannosaurus, that attacked from the rear.

The first Centrosaurus remains were discovered and named by paleontologist Lawrence Lambe in strata along the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada. The name Centrosaurus means "pointed lizard" (from Greek kentron, κέντρον, "point or prickle" and sauros, σαῦρος, "lizard"), and refers to the series of small hornlets placed along the margin of their frills, not to the nasal horns (which were unknown when the dinosaur was named). The genus is not to be confused with the stegosaur Kentrosaurus, the name of which is derived from the same Greek word.

Later, vast bonebeds of Centrosaurus were found in Dinosaur Provincial Park, also in Alberta. Some of these beds extend for hundreds of meters and contain thousands of individuals of all ages and all levels of completion. Scientists have speculated that the high density and number of individuals would be explained if they had perished while trying to cross a flooded river. A discovery of thousands of Centrosaurus fossils near the town of Hilda, Alberta, is believed to be the largest bed of dinosaur bones ever discovered. The area is now known as the Hilda mega-bonebed.

Because of the variation between species and even individual specimens of centrosaurines, there has been much debate over which genera and species are valid, particularly whether Centrosaurus and/or Monoclonius are valid genera, undiagnosable, or possibly members of the opposite sex. In 1996, Peter Dodson found enough variation between Centrosaurus, Styracosaurus, and Monoclonius to warrant separate genera, and that Styracosaurus resembled Centrosaurus more closely than either resembled Monoclonius.

Classification

The genus Centrosaurus gives its name to the Centrosaurinae subfamily. Its closest relatives appear to be Styracosaurus and Monoclonius. It so closely resembles the latter of these that some paleontologists have considered them to represent the same animal. Other members of the Centrosaurinae clade include Pachyrhinosaurus, Avaceratops, Einiosaurus, Albertaceratops, and Achelousaurus,.

The cladogram presented below represents a phylogenetic analysis by Chiba et al. (2017):

Like other ceratopsids, the jaws of Centrosaurus were adapted to shear through tough plant material. The discovery of gigantic bone beds of Centrosaurus in Canada suggest that they were gregarious animals and could have traveled in large herds. A bone bed composed of Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus remains is known from the Dinosaur Park Formation in what is now Alberta. The mass deaths may have been caused by otherwise non-herding animals gathering around a waterhole during a drought. Centrosaurus is found lower in the formation than Styracosaurus, indicating that Centrosaurus was displaced by Styracosaurus as the environment changed over time.

The large frills and nasal horns of the ceratopsians are among the most distinctive facial adornments of all dinosaurs. Their function has been the subject of debate since the first horned dinosaurs were discovered. Common theories concerning the function of ceratopsian frills and horns include defense from predators, combat within the species, and visual display. A 2009 study of Triceratops and Centrosaurus skull lesions found that bone injuries on the skulls were more likely caused by intraspecific combat (horn-to-horn combat) rather than predatory attacks. The frills of Centrosaurus were too thin to be used for defense against predators, although the thicker, solid frills of Triceratops might have evolved to protect their necks. The frills of Centrosaurus were most likely used "for species recognition and/or other forms of visual display".

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org