Sue

“Sue” is the nickname given to FMNH PR 2081, which is the largest, most extensive and best preserved Tyrannosaurus rex specimen ever found at over 90% recovered by bulk. It was discovered in August of 1990, by Sue Hendrickson, a paleontologist, and was named after her. After ownership disputes were settled, the fossil was auctioned in October 1997, for US $7.6 million, the highest amount ever paid for a dinosaur fossil, and is now a permanent feature at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois. It has a length of 12.3 meters (40 ft), stands 3.66 m (12 ft) tall at the hips, and according to the most recent studies estimated to have weighed between 8.4 to 18.5 metric tons when alive. In one of these studies, estimations by Hutchinson et al. (2011) point out to a figure of 13.99 metric tonnes being the average estimate. Authors have stated that their upper [18.5 metric tonnes] and lower [9.5 metric tonnes] estimates were based on models with wide error bars and that they “consider [them] to be too skinny, too fat, or too disproportionate”. Historically older estimations have produced figures as low as 6.4 metric tonnes for this specimen.

Discovery

During the summer of 1990, a group of workers from the Black Hills Institute, located in Hill City, searched for fossils at the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation in western South Dakota near the city of Faith. By the end of the summer, the group had discovered Edmontosaurus bones and was ready to leave. However, a flat tire was discovered on their truck before the group could depart on August 12. While the rest of the group went into town to repair the truck, Sue Hendrickson decided to explore the nearby cliffs that the group had not checked. As she was walking along the base of a cliff, she discovered some small pieces of bone. She looked above her to see where the bones had originated, and observed larger bones protruding from the wall of the cliff. She returned to camp with two small pieces of the bones and reported the discovery to the president of the Black Hills Institute, Peter Larson. He determined that the bones were from a T. rex by their distinctive contour and texture. Later, closer examination of the site showed many visible bones above the ground and some articulated vertebrae. The crew ordered extra plaster and, although some of the crew had to depart, Hendrickson and a few other workers began to uncover the bones. The group was excited, as it was evident that much of the dinosaur had been preserved. Previously discovered T. rex skeletons were usually missing over half of their bones. It was later ascertained that Sue was a record 90 percent complete by bulk. Scientists believe that this specimen was covered by water and mud soon after its death which prevented other animals from carrying away the bones. Additionally, the rushing water mixed the skeleton together. When the fossil was found the hip bones were above the skull and the leg bones were intertwined with the ribs. The large size and the excellent condition of the bones were also surprising. The skull was nearly five feet long (1394 millimeters), and most of the teeth were still intact. After the group completed excavating the bones, each vertebra was covered in burlap and coated in plaster, followed by a transfer to the offices of The Black Hills Institute where preparators began to clean the bones.

Dispute and auction

Soon after the fossils were found, a dispute arose over their legal ownership. The Black Hills Institute had obtained permission from the owner of the land, Maurice Williams, to excavate and remove the skeleton, and had, according to Larson, paid Williams US$5,000 for the remains. Williams later claimed that the money had not been for the sale of the fossil and that he had only allowed Larson to remove and clean the fossil for a later sale. Williams was a member of the Sioux tribe, and the tribe claimed the bones belonged to them. However, the property that the fossil had been found within was held in trust by the United States Department of the Interior. Thus, the land technically belonged to the government. In 1992, the FBI and the South Dakota National Guard raided the site where The Black Hills Institute had been cleaning the bones and seized the fossil. The government transferred the remains to the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, where it was stored until the legal dispute was settled. After a lengthy trial, the court decreed that Maurice Williams retained ownership, because as a beneficiary he was protected by the law against an impulsive selling of real property, and the remains were returned in 1995. Williams then decided to sell the remains, and contracted with Sotheby’s to auction the property. Many were then worried that the fossil would end up in a private collection where people would not be able to observe it. The Field Museum in Chicago was also concerned about this possibility, and decided to attempt to purchase Sue. However, the organization realized that they might have had difficulty securing funding and requested that companies and private citizens provide financial support. The California State University system, Walt Disney Parks and Resorts, McDonald’s, Ronald McDonald House Charities, and individual donors agreed to assist in purchasing Sue for The Field Museum. On October 4, 1997, the auction began at US$500,000; less than ten minutes later, The Field Museum had purchased the remains with the highest bid of US$7.6 million. The final cost after Sotheby’s commission was US$8,362,500. Williams received the $7.6 million tax free due to being a sale of Trust Land.

Preparation

The Field Museum hired a specialized moving company with experience in transporting delicate items to move the bones to Chicago. The truck arrived at the museum in October 1997. Two new research laboratories funded by McDonald’s were created and staffed by Field Museum preparators whose job was to slowly and carefully remove all the rock, or “matrix”, from the bones. One preparation lab was at the Field Museum itself, the other was at the newly opened Animal Kingdom in Disney World in Orlando. Millions of visitors observed the preparation of Sue’s bones through glass windows in both labs. Footage of the work was also put on the museum’s website. Several of the fossil’s bones had never been discovered, so preparators produced models of the missing bones from plastic to complete the exhibit. The modeled bones were colored in a purplish hue so that visitors could observe which bones were real and which bones were plastic. The preparators also poured molds of each bone. All the molds were sent to a company outside Toronto to be cast in hollow plastic. Field Museum kept one set of disarticulated casts in its research collection. The other sets were incorporated into mounted cast skeletons. One set of the casts was sent to Disney’s Animal Kingdom in Florida to be presented for public display. Two other mounted casts were placed into a traveling tour that was sponsored by the McDonald’s Corporation.

Once the preparators finished removing the matrix from each bone, it was sent to the museum’s photographer who made high-quality photographs. From there, the museum’s paleontologists began the study of the skeleton. In addition to photographing and studying each bone, the research staff also arranged for CT scanning of select bones. The skull was too large to fit into a medical CT scanner, so Boeing’s Rocketdyne laboratory in California agreed to let the museum use their CT scanner that was normally used to inspect space shuttle parts.

Bone damage

Close examination of the bones revealed that Sue was 28 years old at the time of death—the oldest T. rex known until Trix was found in 2013. A Nova episode said that the death occurred in a seasonal stream bed, which washed away some small bones. During life, this carnivore received several injuries and suffered from numerous pathologies. An injury to the right shoulder region of Sue resulted in a damaged shoulder blade, a torn tendon in the right arm due most likely from a struggle with prey, and three broken ribs. This damage subsequently healed (though one rib healed into two separate pieces), indicating Sue survived the incident. The left fibula is twice the diameter of the right one, likely a result of infection. Original reports of this broken bone were contradicted by the CT scans which showed no fracture. Multiple holes in the front of the skull were originally thought to be bite marks by some. A subsequent study found these to be areas of infection instead, possibly from an infestation of an ancestral form of Trichomonas gallinae, a protozoan parasite that infests birds and ultimately leads to death by starvation due to internal swelling of the neck. Damage to the back end of the skull was interpreted early on as a fatal bite wound. Subsequent study by Field Museum paleontologists found no bite marks. The distortion and breakage seen in some of the bones in the back of the skull was likely caused by post-mortem trampling. Some of the tail vertebrae are fused in a pattern typical of arthritis due to injury. The animal is also believed to have suffered from gout. Scholars debate exactly how the animal died; the cause of death is ultimately unknown.

Exhibition

After the bones were prepared, photographed and studied, they were sent to New Jersey where work began on making the mount. This work consists of bending steel to support each bone safely and to display the entire skeleton articulated as it was in life. The real skull was not incorporated into the mount as subsequent study would be difficult with the head 4 m (13 ft) off the ground. Parts of the skull had been crushed and broken and thus appeared distorted. This also provides scientists with easier access to the skull as they continue to study it. The museum made a cast of the skull, and altered this cast to remove the distortions, thus approximating what the original undistorted skull may have looked like. The cast skull was also lighter, allowing it to be displayed on the mount without the use of a steel upright under the head. The original skull is exhibited in a case that can be opened to allow researchers access for study. Originally, the Field Museum had plans to incorporate SUE into their preexisting dinosaur exhibit on the second floor, but had little left in their budget to do so after purchasing it. Instead, the T.rex was put on display near the entrance on the first floor of the museum where it would remain for the next 18 years.

Sue was unveiled on May 17, 2000, with more than 10,000 visitors. John Gurche, a paleoartist, painted a mural of a Tyrannosaurus for the exhibit.

New suite (2019)

In early 2018, Sue was dismantled and moved to its own gallery in the Evolving Planet exhibit hall. Opened on December 21, 2018, the reassembly is intended to reflect the newest scientific theories, as well include the proper furcula and attachment of the gastralia to the rest of the skeleton. The new, 5,100 square-foot exhibit includes animated videos of Sue that are projected in 6K onto nine-foot tall panes behind its skeleton. Atlantic Productions worked with the Field Museum, as well as Chicago's Adler Planetarium, to create multiple animated sequences, including Sue scavenging an Ankylosaurus carcass, battling a Triceratops, and hunting an Edmontosaurus. According to the Field Museum's curator of dinosaurs, paleontologist Pete Makovicky, the suite was designed to accentuate the size and stature of Sue, and although smaller, the exhibit allows for a more intimate display of the T. rex. Along with the skull of a Triceratops and other Cretaceous period artifacts, such as shark teeth and pachycephalosaurid bones. Sue's real skull is studied so often that it is kept in a separate display in the exhibition.

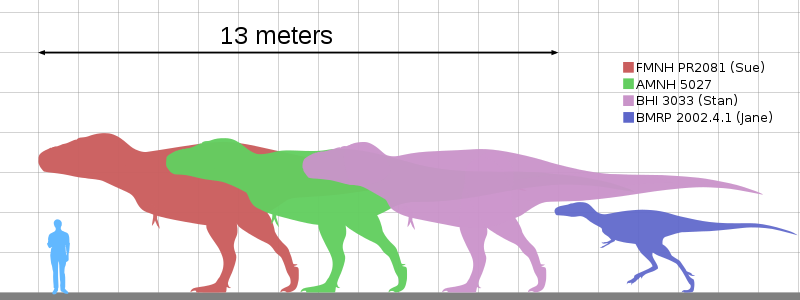

Size

Sue has a length of 12.3 meters (40 ft), stands 3.66 m (12 ft) tall at the hips, and has in 2011 been estimated by Hutchinson e.a. at between 9.5–18.5 metric tons (10.5–20.4 short tons), though the authors stated that their upper and lower estimates were based on models with wide error bars and that they “consider them [these extremes] to be too skinny, too fat, or too disproportionate”. Another recent estimate portraying a leaner build placed the specimen at 8.4 metric tons (9.3 short tons). Historically more out of date estimations placed this specimen as low as 6.4 metric tons (7.1 short tons) in weight. Currently this is the largest known complete tyrannosaur specimen on record.

In the media

A 1997 episode of the PBS show Nova, “Curse of the T. Rex”, discussed the history of the discovery and ensuing legal challenges.

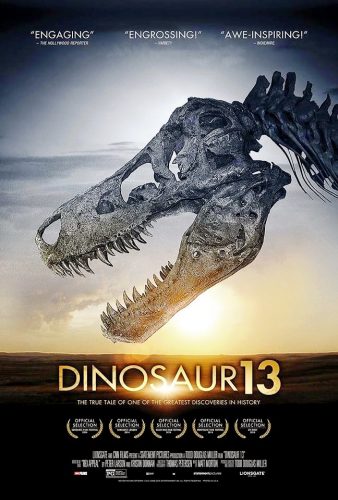

Director Todd Miller’s documentary Dinosaur 13, which is about Sue’s discovery and subsequent legal actions, appeared at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival.

In Jim Butcher’s novel Dead Beat, protagonist Harry Dresden raises Sue from the dead as a massive zombie and uses her as a steed during part of the final battle of the book.

In Richard Polsky’s nonfiction book Boneheads: My Search for T. Rex, Polsky travels to Faith, South Dakota, and meets with Peter Larson and Maurice Williams to write about the search, discovery, and legal battle over Sue, and to search for another T.rex on Williams’s ranch.

The children’s computer game I See Sue engages children in the lives of the dinosaurs. They play a turn-based tile-match board game for the reward of seeing Sue. The game was published by Simon and Schuster Interactive and created by GamesThatWork under the guidance of Field Museum.

The fantasy/promotional web series Lil BUB’s Big SHOW included a Halloween-based episode where cat host Lil Bub pays a visit to the Field Museum, checking the animal exhibits there. After Lil Bub notices Sue, she becomes infatuated with Sue’s perfection as a T-Rex skeleton. Sue later calls in Lil Bub at her studio, and instantly turns Lil Bub’s infatuation to horror when Sue reveals its fondness for eating cats.

2015 episode 660 of NPR’s Planet Money concerning the economics of Dinosaur Bones.

Source: www.wikipedia.com