Permian Mass Extinction

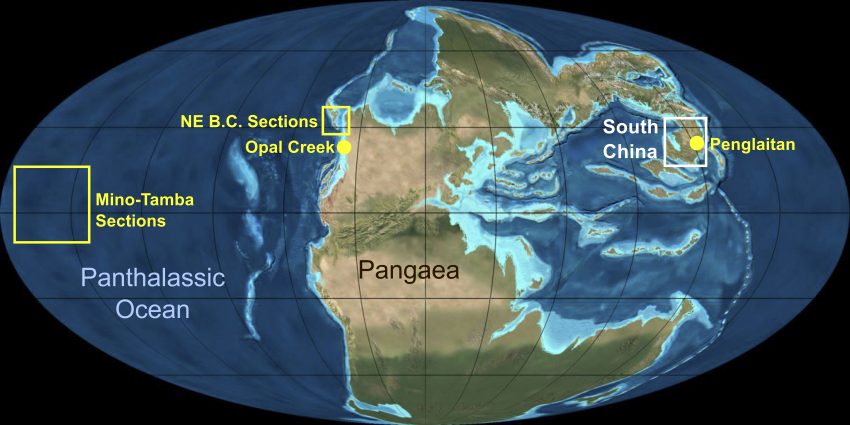

The Permian–Triassic (P–Tr or P–T) extinction event, colloquially known as the Great Dying, the End-Permian Extinction or the Great Permian Extinction, occurred about 252 Ma (million years) ago, forming the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, as well as the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras. It is the Earth’s most severe known extinction event, with up to 96% of all marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species becoming extinct. It is the only known mass extinction of insects. Some 57% of all families and 83% of all genera became extinct. Because so much biodiversity was lost, the recovery of life on Earth took significantly longer than after any other extinction event, possibly up to 10 million years, although studies in Bear Lake County near the Idaho city of Paris showed a quick and dynamic rebound in a marine ecosystem, illustrating the remarkable resiliency of life.

There is evidence for one to three distinct pulses, or phases, of extinction. Suggested mechanisms for the latter include one or more large meteor impact events, massive volcanism such as that of the Siberian Traps, and the ensuing coal or gas fires and explosions, and a runaway greenhouse effect triggered by sudden release of methane from the sea floor due to methane clathrate dissociation or methane-producing microbes known as methanogens; possible contributing gradual changes include sea-level change, increasing anoxia, increasing aridity, and a shift in ocean circulation driven by climate change.

Causes

Pinpointing the exact cause or causes of the Permian–Triassic extinction event is difficult, mostly because the catastrophe occurred over 250 million years ago, and since then much of the evidence that would have pointed to the cause has been destroyed by now or is concealed deep within the Earth under many layers of rock. The sea floor is also completely recycled every 200 million years by the ongoing process of plate tectonics and seafloor spreading, leaving no useful indications beneath the ocean.

Scientists have accumulated a fairly significant amount of evidence for causes, and several mechanisms have been proposed for the extinction event. The proposals include both catastrophic and gradual processes (similar to those theorized for the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event).

- The catastrophic group includes one or more large bolide impact events, increased volcanism, and sudden release of methane from the sea floor, either due to dissociation of methane hydrate deposits or metabolism of organic carbon deposits by methanogenic microbes.

- The gradual group includes sea level change, increasing anoxia, and increasing aridity.

Any hypothesis about the cause must explain the selectivity of the event, which affected organisms with calcium carbonate skeletons most severely; the long period (4 to 6 million years) before recovery started, and the minimal extent of biological mineralization (despite inorganic carbonates being deposited) once the recovery began.

End of the Permian period

Start of the Triassic period