Russian Paleontologists Discover New Giant Herbivorous Sauropod: Volgatitan simbirskiensis

Paleontologists from Russia have described a new dinosaur, the Volgatitan. Seven of its fossilized vertebrae, buried in the ground for about 130 million years, were found on the banks of the Volga, not far from the village of Slantsevy Rudnik, five kilometers from Ulyanovsk. The study has been published in the latest issue of Biological Communications.

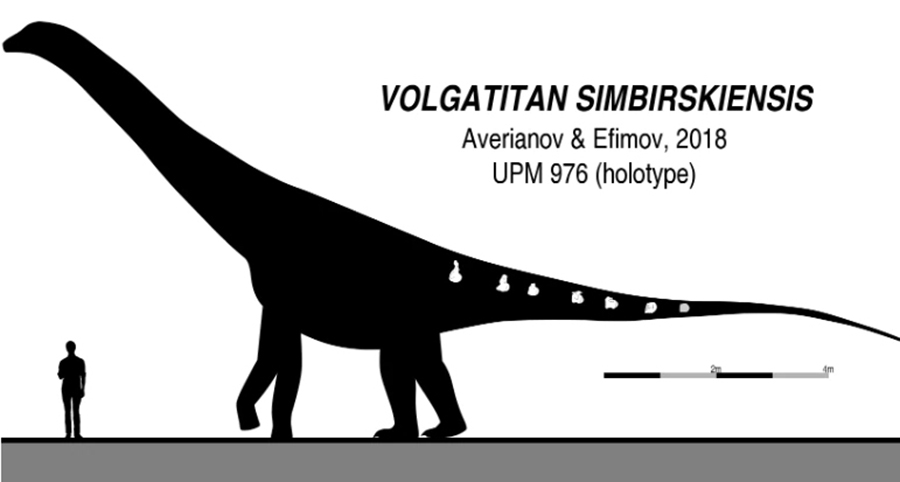

The Volgatitan belongs to the group of sauropods—giant herbivorous dinosaurs with a long necks and tails, which lived about 200 to 65 million years ago. Weighing around 17 tons, the ancient reptile from the banks of the Volga was not the largest among its relatives. The scientists described it from seven caudal vertebrae. The bones belonged to an adult dinosaur characterized by neural arches (parts of the vertebrae protecting the nerves and blood vessels), which completely merged with the bodies of the vertebrae.

The remains of the dinosaur were discovered near the village of Slantsevy Rudnik. This is where, in 1982, Vladimir Efimov discovered three large vertebrae that had fallen out of a high cliff. Later, in 1984-1987, three nodules of limestone fell off, which contained the remaining vertebrae. In his works, the head of the Undorovsky Paleontology Museum called the unusual finds "giant vertebrae of unknown taxonomic affiliation."

Alexander Averianov said, "In the early 1990s, Vladimir Efimov showed photographs of the bones to Lev Nesov, a well-known Leningrad paleontologist. Lev Nesov thought that the vertebrae belonged to sauropods, giant herbivorous dinosaurs. In 1997, Vladimir Efimov published a preliminary note about this find in the Paleontological Journal. He referred to the vertebrae as a sauropod of the Brachiosauridae family. Last July, I finally managed to visit him in Undory and study the bones, and also managed to determine that they belonged to the new taxon of titanosaurs."

The dinosaur received a scientific name—Volgatitan simbirskiensis. It comes from the Volga River and the city of Simbirsk (currently, Ulyanovsk). Titans are ancient Greek gods known for their large size. Therefore, according to a paleontological tradition, this word is used in many scientific names of sauropods from the group of titanosaurs. It is also part of the name of the group.

Today, along with the Volgatitan from Russia, 12 valid dinosaur taxa have been described. There are only three sauropods among them: Tengrisaurus starkovi, Sibirotitan astrosacralis and Volgatitan simbirskiensis. The first two are the first sauropods in Russia, which were also studied by St. Petersburg University scientists in 2017. According to Aleksandr Averianov, the description of dinosaur taxa in recent years has become possible due to progress in understanding the anatomy and phylogeny of dinosaurs. In addition, the Russian sauropod allowed scientists to learn more about how these species of ancient reptiles had lived and developed.

"Previously, it was believed that the evolution of titanosaurs took place mainly in South America, with some taxa moving into North America, Europe and Asia only in the Late Cretaceous," explained the St. Petersburg University professor. In Asia, representatives of a broader group of titanosauriform, such as the recently described Siberian titanium, dominated in the early Cretaceous. However, the recent description of the Tengrisaurus from the Early Cretaceous of Transbaikal Region and the finding of the Volgatitan indicate that titanosaurs in the Early Cretaceous were distributed much more widely; and, perhaps, important stages of their evolution took place in Eastern Europe and Asia."

More information: et al, The oldest titanosaurian sauropod of the Northern Hemisphere, Biological Communications (2018). DOI: 10.21638/spbu03.2018.301

Provided by: AKSON Russian Science Communication Association

Source: https://phys.org