Once Implicated in Cloning Fraud, This Scientist Now Wants to Bring Back an Extinct Ice-Age Horse

In 2004, Woo-suk Hwang fooled the scientific community. Now he wanted to bring a species back to life.

It's an idea with Jurassic Park-level ambitions: cloning a mummified 40,000-year-old horse to bring the extinct species back to life. Many experts are highly skeptical, to put it lightly. And at the center of the controversy is Woo-suk Hwang, a research who was part of a major scientific fraud scandal about cloning a decade ago.

The story begins back in the Ice Age, when a baby horse died at the the approximate age of two months in what scientists suspect was an accident, likely a drowning. About 40,000 years late, in August 2018, scientists at Yakutian North-Eastern Federal University studying the horse's mummified remains found that the region's permafrost had kept the foal in amazing condition. "Even its hair preserved, which is incredibly rare for such ancient finds," said Yakutia Mammoth museum curator Semyon Grigoryev, speaking to The Siberian Times.

The horse belonged to a species known as Equus lenensis, or "Lena Horse." It shares more in common with the ancient wild Yukon horses of North America than it does with the current horses that occupy this bitterly cold region, which are known as Yakutian horses and have been domesticated since the 13th century.

Now things have gotten truly odd. A group of Russian and South Korean scientists think that can clone it.

“If we find only one live cell, we can clone this ancient horse,” says Woo-suk Hwang, one of the South Korean scientists involved, to The Siberian Times. “We can multiply it and get as many embryos as we need.”

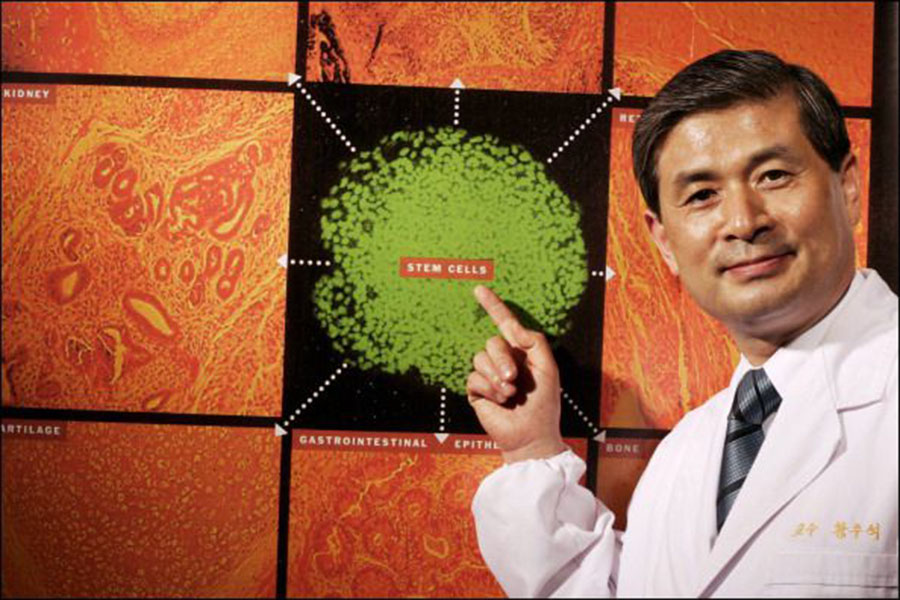

If Hwang's name sounds familiar, it's because he has a curious history with cloning claims. A veterinarian by trade who first gained acclaim for cloning pets in the 90s, Hwang rose to scientific stardom in 2004 when he and his colleagues claimed to have created the world’s first cloned human embryos, and furthermore, that they had extracted stem cells from them.

Hwang continued to bombastic claims about his embryos until 2006, when his collaborators and online researchers both presented incontrovertible evidence that he committed extreme ethical lapses in obtaining the cells and had falsified data. The president of Seoul National University, where Hwang had been doing his work, called the episode “an unwashable blemish on the whole scientific community as well as our country.”

Hwang has been trying for a comeback ever since. He has never claimed responsibility for nine of 11 scientific papers related to human embryos that were shown to be fraudulent, but remains an expert on the animal cloning process. For years he has run the Sooam Biotech Research Foundation, which has successfully cloned dogs, cows, pigs and coyotes. But some experts wonder if Hwang's claims about the ancient wild horse were simply a new attention grab.

Cloning a modern day creature—say, a coyote—is possible because the coyote's DNA is fully intact. That's simply not the case with Ice Age DNA. It's typically been degraded "into tens of millions of pieces," Love Dalén, a professor of evolutionary genetics at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, tells LiveScience. Similar challenges would exist with trying to clone a woolly mammoth or other extinct species. Hwang says he is undeterred. Speaking to The Siberian Times, he says, "if we manage to clone the horse, it will be the first step to cloning the mammoth."

The odds are long, but not impossible. Scientists concede that if Hwang and his team were able to find enough workable DNA from the ancient foal, then cloning it stands a chance at being scientifically feasible. Considering Hwang's history with bold claims, though, they're not holding their breath.

Source: LiveScience / www.popularmechanics.com