16 Fascinating Extinct Animals

Major extinction events are nothing new for the planet, but species are now dying out at an alarming rate thanks to humans.

We are presently losing dozens of species every day, according to the Center for Biological Diversity. Nearly 20,000 species of plants and animals are at a high risk of extinction and if trends continue, Earth could see another mass extinction event within a few centuries.

Tasmanian Tiger

The Tasmanian tiger was listed as extinct nearly 80 years ago, but now a team of British naturalists are on the prowl to prove that the species is still alive.

Properly named a thylacine, the “Tassie tiger” is the largest known carnivorous marsupial of modern times. The stripes on its back resemble those of the jungle cat after which it is named. Though the last known thylacine died at Hobart Zoo in Tasmania on Sept. 7, 1936, some believe the animal is alive and well in the island state’s remote northwestern region.

While the Tasmanian government has stated there is “no conclusive evidence” that the thylacine exists, a team from the U.K.’s Centre for Fortean Zoology is scouring the Tasmanian topography in hopes of gathering more evidence to prove the animal still roams.

We hope the team is successful in finding the long-lost Tasmanian tiger. Until then, they’ll remain on this list of fascinating extinct animals.

Dodo

For many of us, the dodo is the first creature that comes to mind when we think of extinct animals. In popular culture, it is the archetypal example of extinct species, to the point that “gone the way of the dodo” has become a common idiom referring to the extinction or obsolescence of almost anything.

First discovered by modern humans around 1600, these unique-looking birds existed in limited areas free from natural predators. That means that when humanity finally did come calling, dodos were unusually fearless (and therefore stupidly trusting) of us. This, combined with their flightlessness, made the birds easy pickings for hungry sailors.

And in our bullying human arrogance, we not only made dodos extinct, but also bestowed upon them a reputation for being dumb, simply because they thought we might actually be kind to them.

California Golden Bear

The noble California golden bear, like the Japanese river otter, is held in high esteem as a symbol of the place that gave it its name. This subspecies of brown bear is the one you’ll find on the official state flag of California. Specifically, the bear depicted on the flag is based on Monarch, the last California golden bear held in captivity, whose taxidermied body remains preserved today at the Academy of Sciences at Golden Gate Park. The California golden bear also serves as the mascot of the UC Berkeley California Golden Bears and the UCLA Bruins. Of course, all this veneration didn’t keep the last living California golden bear from being shot and killed in 1922.

Japanese River Otter

In 2012, Japan’s Ministry of the Environment declared the Japanese river otter extinct. Once numbering in the millions, the population of river otters collapsed due to overhunting and habitat destruction by humans. The last time a Japanese river otter was seen was in 1979. Attempts to find more of the animals were conducted over the past few decades, but on Aug. 28, 2012, the Japanese government officially gave up hope.

Aurochs

The aurochs was the original cow, literally. These beasts were the larger, wild progenitors of the modern, domestic cattle we know today. An ancient animal, the oldest evidence of aurochs known to man dates from about 2 million years ago during the Pleistocene, and they were first domesticated some 10,000 years ago. Once found all over the world, the aurochs’ range was limited to just a few countries in Central and Eastern Europe by the 1200s. Conservation efforts were made with the hunting of aurochs being outlawed, but the population dwindled to almost nothing by the 17th century. The last living aurochs died in a Polish nature preserve in 1627.

Golden Toad

These beautiful amphibians only very recently disappeared from Earth. In fact, golden toads were first discovered less than 50 years ago, when herpetologist Jay Savage found them in 1966. The toads’ yellow-orange glow was so striking that Savage at first did not believe it was natural, saying that he thought some jokester must have painted them that color. In the 20 years following their discovery, approximately 1,500 golden toads were observed. Then they seemed to disappear suddenly and completely. Zero of them have been seen since 1989. Climate change is considered the culprit.

Blue Buck

Here’s an example of an animal whose extinction we can’t really blame on ourselves, because they were already quite rare by the time humankind found them. The bluebuck, a species of large antelope, was first discovered in the 1600s at the southern tip of Africa, to which its range already was limited. Evidence suggests their numbers first dropped dramatically some 2,000-3,000 years ago due to natural climate change affecting the landscape and the bluebucks’ food sources. Once modern humans discovered bluebucks, they already were on their way out, so don’t feel too guilty about it.

Great Auk

The great auk was a large, flightless, penguin-like bird with a unique-looking beak. Although great auks resemble penguins, the two species are not related. (The great auk’s closest relative is the still-existing, though threatened, razorbill.) What’s interesting, however, is that the great auk was known centuries before penguins were discovered, and originally, the word “penguin” was used as a nickname for great auks. When explorers later discovered penguins, they gave them their name due to their similar appearance to great auks. Sadly, hunting crippled the great-auk population, and despite a couple centuries of protection, the species died out. The last time any human saw a great auk was in the 1850s. Today, everyone’s favorite animal is the penguin, but few know of the now-extinct bird that gave penguins their name.

Baiji

Another very recently extinct species, the baiji (aka the Chinese river dolphin) was a victim of hunting and modern industrialization, i.e., it’s our fault they’re gone. At one time, these dolphins were an especially admired animal in Chinese culture, but this view was officially denounced by the Chinese government in the 1950s during a period of economic expansion, and the animals were then openly hunted. With their numbers already at only about 6,000 dolphins, the baiji population collapsed due to hunting, fishing, pollution and loss of habitat. Within decades, their numbers were reduced to only a few hundred. Despite conservation efforts that began in the ’70s, no baiji has been seen since 2004, and the species was declared “functionally extinct” in 2006.

Haast’s Eagle

The great Haast’s eagle, named for the man who first classified the species in 1870, is the largest eagle known to have ever existed on Earth. The enormous raptors lived in New Zealand, where they happily hunted and ate the island’s large, flightless moa birds as their main food source. Unfortunately, moa also were happily hunted and eaten by the Maori, the indigenous humans of New Zealand. In fact, Haast’s eagles and the Maori people were the exclusive predators of moa. Yet all that happy hunting and eating was still enough to drive the moa to extinction by 1400. The ever-adaptable humans had other food sources, of course, but the Haast’s eagles weren’t so lucky. With no more food, they likewise became extinct almost immediately.

Huia

Like the Haast’s eagle and the moa, the huia was a species of bird that lived in New Zealand. While the Maori people hunted moa almost exclusively for food, they celebrated and venerated the huia birds for their beautiful plumage and cool beaks. But they still expressed their veneration the same way: hunting. After all, that sweet huia plumage made for some pretty awesome ornaments and hair decorations. Still, the Maori aren’t responsible for hunting the huia into extinction. That came later, when Europeans arrived, overhunting the unique birds and clearing the forests that served as huia habitats. The huia were further polished off by disease, parasites and animals like cats and rats, all of which also were brought along by those pesky Europeans.

Laughing Owl

Here a sub-theme emerges as we look at yet another extinct bird native to New Zealand. Before it was overhunted to extinction by Europeans and the animals they introduced, the laughing owl was a cool-looking bird noted for its shrieking cry that was said to sound like barking or laughter. But we shall never hear that sound again. Or will we? The laughing owl’s story may not be over. A group of American tourists were visiting New Zealand in the 1980s when, far from civilization, they were frightened by the sound of cackling laughter. Years later, one of the tourists had occasion to relate the story to a New Zealand ornithologist who was excited to hear what he knew to be a description of a laughing owl. The story may be hard to prove, but we remain cautiously optimistic that humans will be terrified by the screech of laughing owls again someday.

Quagga

Party in the front, all business in the back: that’s what the quagga — a type of zebra with stripes only on its front half — was all about. Zebras come in a variety of colors and patterns, and no two are alike, so years ago it wasn’t clear whether quaggas were differently patterned zebras or actually a species unto themselves. The animals were hunted to extinction by the late 19th century, before the mystery could be solved. Later, however, DNA samples revealed that quaggas were in fact not a separate species, but a subspecies of the plains zebra with which we’re familiar today. As a result, there is an ongoing effort to recreate the quagga through selective breeding. In recent years, this effort has met with some success.

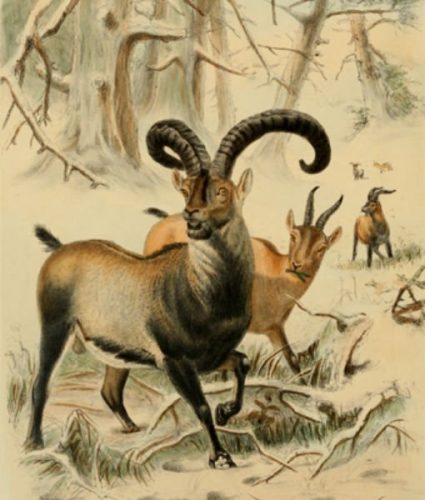

Pyranean Ibex

Here’s another extinct animal whose fate may not be sealed. Pyrenean ibexes were once numerous, but for reasons that aren’t currently understood by scientists, their numbers dwindled to fewer than 100 by the 20th century. The last Pyrenean ibex died in 2000, and then the animal was extinct. However, this species is the first in history to be made “unextinct” through the intervention of humankind and our wild technology. Nine months after the last Pyrenean ibex fell, a project was announced that would clone the species. After several years of failed attempts, a cloned Pyrenean ibex was born to a mountain-goat surrogate mother in 2009. Sadly, the animal died within minutes, but not before living its incredibly short life as an unprecedented scientific marvel.

Falkland Islands Wolf

This extinct canid was kind of like a wolf, kind of like a dog, and kind of like a fox. (In fact, it is sometimes called the Falkland Islands dog or the Falkland Islands fox.) Like our friends the bluebucks, Falkland Islands wolves already existed in fairly limited quantities over a relatively tiny range by the time humanity found them. And like dodos, they didn’t do themselves any favors with a tame temperament that made them unusually trusting of humans. The species is notable for having been studied by Charles Darwin, who upon visiting the Falkland Islands in 1833, guessed that the species would become extinct very quickly. Sadly, he was proven correct within 40 years.

Rocky Mountain Locust

Many now-extinct species were once numerous, but Rocky Mountain locusts were the mostnumerous. Covering the western half of the United States at their apparent peak in the late 1800s, the largest swarm of Rocky Mountain locusts ever seen is estimated to have numbered more than 12 trillion of the insects, covering almost 200,000 square miles, an area twice the size of Colorado. This still holds the Guinness World Records distinction as the greatest concentration of any animal. Yet 30 years later, they were extinct. Our best guess at the reason is that, between the locusts’ swarming periods, American farmers dug and plowed the land that contained all their eggs. Oops. Considering that that huge swarm in the 1870s damaged farmland in the U.S. to the tune of $200 million, maybe this is one extinction we don’t have to regret too hard.

All images via Wikimedia. Source: www.NatGeo.com