How Do We Know Birds Are Dinosaurs?

Birds aren’t descended from dinosaurs. They are dinosaurs.

Ferocious tyrannosaurs and towering sauropods are long gone, but dinosaurs continue to frolic in our midst. We’re talking about birds, of course, yet it’s not entirely obvious why we should consider birds to be bona fide dinos. Here are the many reasons why.

Make no mistake, birds are legit dinosaurs, and not some evolutionary offshoot. All non-avian dinosaurs were wiped out following the asteroid-induced mass extinction 66 million years ago, but some species of birds—probably ground-dwelling birds—managed to survive, and they wasted no time in taking over once their relatives were gone.

“Those little guys singing outside your window are the dinosaurs we have left these days,” Adam Smith, curator at Clemson University’s Campbell Geology Museum, explained in an email. “Birds are just one type of dinosaur. Saying ‘birds descended from dinosaurs’ is akin to saying that people descended from mammals. Simply put, all birds are dinosaurs, but not all dinosaurs are birds.”

That birds are somehow connected to dinosaurs is hardly a recent revelation. In the late 19th century, English naturalist Thomas Henry Huxley dared to suggest that birds evolved from dinosaurs. As science writer Riley Black wrote in 2010, his ideas about the origin of birds “were not a perfect anticipation of our current knowledge,” but Huxley, an adept anatomist, was clearly onto something.

Indeed, scientists have since identified a host of features that comfortably position as birds as dinosaurs in the phylogenetic tree. Kate Lyons, an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska’s Lincoln School of Biological Sciences, says there “isn’t just one smoking gun” that allows paleontologists to say birds are dinosaurs, as there are “multiple pieces of evidence” that point to this conclusion, as she wrote to me in an email.

Paleontologist Steven Brussatte from the University of Edinburgh says we know birds are dinosaurs by applying the same reasoning that tells us bats are mammals.

“Yes, birds are small, and have feathers, and wings, and fly, and that is different from the image of dinosaurs we’re used to,” he wrote in an email. “Bats are the mammalian analogy—they are small, have wings, and fly, and they don’t look anything like a dog or elephant or primate, but they are mammals nonetheless.”

Indeed, bats feature many traits exclusive to mammals, like hair, molar teeth, three tiny ear bones, and the ability to feed young with milk. Likewise, birds have features that are only seen in theropod dinosaurs, Brussatte explained.

Like feathers.

Indeed, while there’s no single “smoking gun” to pin birds down as dinosaurs, the presence of feathers is probably the most smoking gunniest thing of all. The fossil record is filled with examples of feathered non-avian dinosaurs, and because feathers are unique to birds, scientists are able to link them both together as dinosaurs.

Skeptics may argue that the emergence of feathers in both birds and non-avian dinosaurs is a consequence of convergent evolution, in which similar traits appear independently in unrelated species. Smith says convergent evolution is unlikely in this case because “many of the non-avian dinosaurs that were found with preserved feathers are the exact species that were already, independently hypothesized to be close relatives of birds,” including Velociraptors and Sinosauropteryx.

To which he added: “Feathers are ridiculously complex structures, and while convergent evolution frequently results in similar structures—and even entire animals—that appear on the surface to be quite alike, there aren’t any examples of convergent evolution duplicating structures on that scale, with that sort of fidelity.”

Phylogenetics—the study of the evolutionary relationships between species—provides further evidence that birds are dinosaurs, as Andre Rowe, a PhD student from the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol, explained in an email. With all due respect to Jurassic Park, paleontologists aren’t able to extract and analyze ancient dinosaur DNA, but they can examine the key characteristics shared between species as indicated by their skeletons and anatomy. Based on these key characteristics, scientists “can say with near certainty that birds belong to the theropod dinosaur lineage,” said Rowe, in reference to meat-eating dinosaurs like T. rex, Allosaurus, and Compsognathus. Importantly, skeletons of theropods and birds show “no sudden changes in their evolutionary relationship, but rather a smooth transition over millions of years,” he added.

“Taking a trip back in time, we can trace the evolution of the basic bird body plan all the way back to some of the earliest dinosaurs,” wrote Kristi Curry Rogers, a vertebrate paleontologist at Macalester College in Minnesota, in an email. “Just like dinosaurs, birds walk with their legs held directly underneath their bodies, and dinos gave birds an extra little boost in growth rates.”

Holly Woodward Ballard, an associate professor of paleontology and anatomy at the University of Oklahoma, put it this way: “We know birds are dinosaurs because they share more characteristics with extinct dinosaurs than other living animal groups do.”

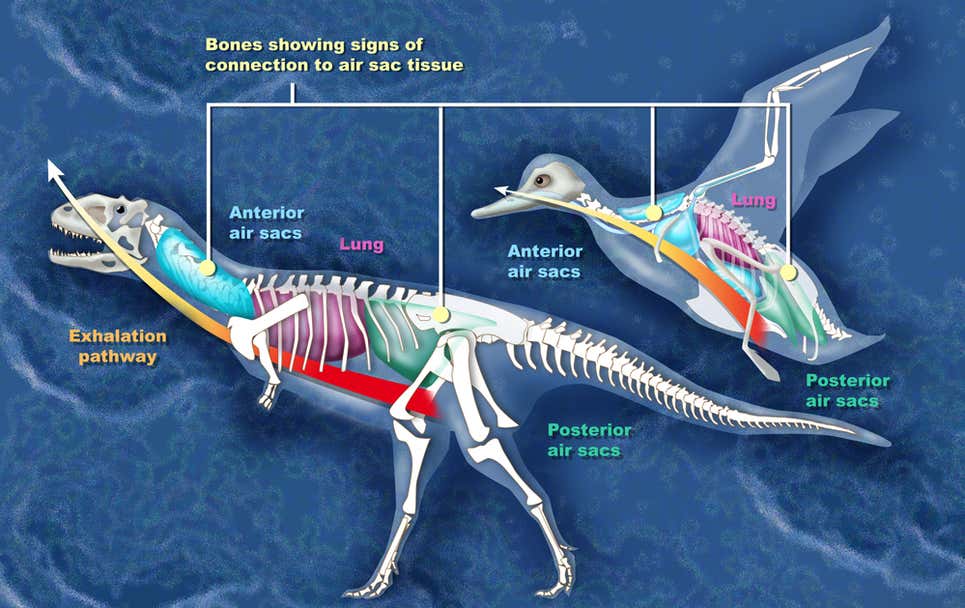

Indeed, there are many other features to consider—things like “wishbones, bones hollowed out by air sacs, and wrists that can rotate,” allowing dinosaurs to “fold their arms up against their bodies,” according to Brussatte.

In an email, paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Jessica Theodor from the University of Calgary described these and other dino-specific features. For example, the structure that allows birds to bend their hands backward at the wrist, which they do to fold their wings, is also found in the arms of wingless coelurosaurs, and biologists can trace the modification of this structure “through theropod evolution,” she explained.

Kat Schroeder, a PhD student from the Department of Biology at the University of New Mexico, described the fusion of certain vertebrae into the synsacrum and pygostyle as one of the most significant evolutionary adaptations in birds.

“The synsacrum is the fusion of the vertebrae over the hips, which stiffens the back and helps with flight, and the pygostyle is a fusion of the last caudal vertebrae that supports tail feathers, which is actually found in some non-avian dinosaurs like Oviraptorosaurs and Ornithomimosaurs which may have had feather fans instead of long tails or fans at the tips of their tails,” she wrote in an email.

“Birds have small flanges on their ribs, called uncinate processes, that provide some mechanical advantage to the breathing muscles of the rib cage,” and they’re also found in oviraptors and dromaeosaurs, as Theodor explained. What’s more, “bird skeletons have a number of other structural similarities to dinosaurs in the skeleton, all of which place them together in phylogenetic analyses,” she said.

Evidence of brooding amongst some dinosaurs, in which animals rest over their nests to keep their eggs warm and protected, is a behavior seen in modern birds, as Rowe reminded me. Also, dinosaurs and birds both used gizzard stones (stones that are swallowed to aid in digestion), “as the stones would grind up food that had already been ingested,” he said.

As I mentioned earlier, scientists can’t study ancient dinosaur DNA, but they can study modern dinosaur DNA.

“The evidence that birds are really just tiny little dinosaurs that learned to fly comes from the dinosaur fossil record as well as from the bodies and genomes of living birds,” Curry Rogers explained. “When we look at modern birds, we can see little mementos of their more ferocious history locked deep inside their genes—extinct developmental programs for building longer tails and teeth.”

To which she added: “It’s all right there—written in the bones and bodies of dinosaurs, living and extinct!”

So the next time a hummingbird comes to your feeder, feel free to greet the tiny bird as a visiting dinosaur. You can likewise claim to have tasted dinosaurs after munching on some chicken wings, or that you were attacked by a dinosaur when a goose frightened you away from her nest. And when the Toronto Blue Jays face off against the Baltimore Orioles, you’re totally good to refer to the matchup as the battle of the dinos.

It’ll sound strange, but you have the science to back you up.

Source: https://gizmodo.com/