The Top Ten Dinosaur Discoveries of 2020

Paleontologists uncovered a great deal about the “terrible lizards” in 2020.

There’s never been a better time to be a dinosaur fan. Even in a year where fossil explorations have been curtailed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, paleontologists have dug deep to describe dozens of new species and unlock new secrets about our favorite prehistoric creatures. The discoveries continue even now, with the fluffy “maned” dinosaur Ubirajara named just last weekend. As we anticipate what the fossil record might reveal in 2021, here’s a look back at ten dinosaur discoveries that surprised and enthralled dinosaur enthusiasts this year.

Tiny Fuzzball Shows How Dinosaurs Started Small

Some of the key traits that allowed dinosaurs to be such an evolutionary success story—from fuzzy feathers to warm-running metabolisms—may have first evolved in their tiny ancestors. This year experts reported the discovery of a tiny reptile from the Triassic of Madagascar they named Kongonaphon. While not a dinosaur itself, this animal was close to the ancestors of both dinosaurs and related flying reptiles called pterosaurs. This small, insect-eating reptile likely moved nimbly to catch lunch and may have sported a coat of fuzz to help regulate its body temperature. This hints that some key dinosaur traits, such as warm-bloodedness and insulating body coverings, evolved early in their history and were elaborated upon as dinosaurs eventually diversified into all sorts of shapes and sizes.

Winner By a Tail

Paleontologists have long suspected that the giant carnivore Spinosaurus spent much of its time around the water. Fossils reported in 2015 went a step further—flat feet and dense bones indicated that Spinosaurus spent a great deal of time in the water and is the first known semi-aquatic dinosaur. This year, a tail added another clue. The appendage, found at the same quarry as the 2015 skeleton, is long and deep. The tail is more like a paddle than what’s seen in other carnivorous dinosaurs and would have been suited to swishy, side-to-side motions that propelled Spinosaurus through the water. The fact that the tail goes with the other fossils found at the site also confirm that they all go to one individual, underscoring the fact that Spinosaurus had strange body proportions unlike any other dinosaur yet discovered.

Dinosaurs Suffered From Cancer, Too

Dinosaurs are often celebrated for being big, fierce and tough. The truth, however, is that they suffered from many of the same injuries and maladies that humans do. A study published this year in The Lancet reported on the first well-documented case of malignant bone cancer in a non-avian dinosaur. The animal, a horned dinosaur known to experts as Centrosaurus, probably coped with declining health before its eventual death in a coastal flood that caught its herd off-guard.

Dinosaurs Weren’t in Decline When the Asteroid Hit

If dinosaurs “ruled the Earth” for millions of years, why were they hit so hard by the mass extinction of 66 million years ago? Paleontologists have been puzzling over this question for decades, and, some have suggested, dinosaurs might have already been dying back by time the asteroid struck. But an increasing amount of evidence contracts that view, including a study published this year in Royal Society Open Science. The researchers looked at different evolutionary trees for what dinosaurs were around during the end of the Cretaceous to track whether dinosaurs were dying out, thriving or staying the same. After sifting through the data, the paleontologists didn’t find any sign that dinosaurs were declining before the asteroid strike. In fact, dinosaurs seemed perfectly capable of evolving new species. If the asteroid had missed, the Age of Dinosaurs would have continued for a very long time.

Taking a Long Swim

Sometimes dinosaurs show up where we don’t expect them. While paleontologists have found numerous fossils of duckbilled dinosaurs at spots around the world—from North America to Antarctica—no one had ever found one in Africa. That changed this year. In a Cretaceous Research study, paleontologists described a new species of hadrosaur found in Morocco. Named Ajnabia, the dinosaur lived at the end of the Cretaceous during a time when Africa was separated from other continents by deep water channels. Swimming would have been the only way for the dinosaur to reach prehistoric Africa from Europe or Asia, reinforcing the idea that exceptional events can help species move between distant continents.

Baby Titans Had Tiny Horns

Baby dinosaurs are exceptionally rare. We know far more about the adults of most species than how they started life. And when we do find those babies, they often hold surprises. An embryo of a long-necked dinosaur called a titanosaur reported in Current Biology drew attention this year for a strange, rhino-like horn jutting from its face. No such structure has been found in adult titanosaurs, and so it seems the horn is a kind of a temporary “egg tooth” that the dinosaur would have used to crack out of its shell.

Were Dinosaur Eggs Soft?

Think of a dinosaur egg and you’re likely to envision something out of Jurassic Park—a hard-shelled capsule the baby dinosaur has to kick or push its way out of. But research published this year in Nature proposes that many dinosaurs laid soft-shelled eggs. Under close examination, the eggs of the dinosaurs Protoceratops and Mussaurus turned out to be more like the leathery eggs of turtles than the thick, hard-shelled eggs known from other dinosaurs. This may indicate that dinosaur eggs started off soft and only later evolved to be hard-shelled in some groups. The findings may often indicate why eggs have been so hard to find for many dinosaur species, as softer eggs would decay more readily than hard-shelled ones.

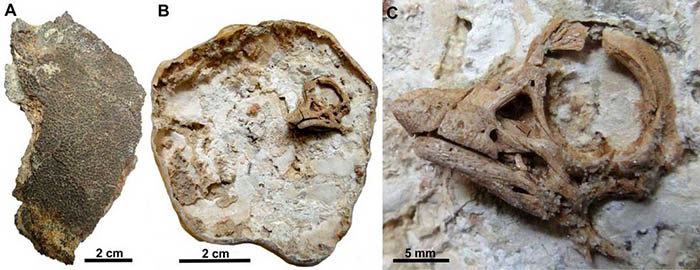

Enter the Wonderchicken

Not all this year’s big dinosaur discoveries had to do with non-avian dinosaurs. A fossil dubbed the “wonderchicken” in Nature has helped paleontologists understand how modern birds took off during the Age of Dinosaurs. While birds go back to about 150 million years ago, the wonderchicken—or Asteriornis—lived about 67 million years ago and is the oldest known representative of what biologists think of as modern birds. The fossil, which includes a skull, has some anatomical similarities to chickens and ducks. These findings indicate that modern birds started to evolve and proliferate prior to the mass extinction that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs. If such beaked, seed-eating birds had not evolved, dinosaurs might have been entirely wiped out instead of leaving birds behind.

The Hunt for Dino DNA

Will DNA from the likes of Tyrannosaurus ever be found? The consensus has been “No,” as DNA decays too fast after death to survive millions and millions of years. But in a study published in National Science Review this year, researchers have proposed that they’ve found chemical signatures consistent with DNA in the bones of a 70 million-year-old hadrosaur called Hypacrosaurus. The results have yet to be expanded upon or verified, but the idea that even degraded DNA from non-avian dinosaurs might survive is tantalizing for all such a discovery might teach us about prehistoric life.

Polar Dinosaurs Remained Year Round

Ever since paleontologists discovered dinosaur bones within the ancient Arctic Circle, experts have debated whether the polar dinosaurs stayed in their cool habitats year-round or migrated with the seasons. A tiny jaw from a young dinosaur now answers that question. Described in PLOS ONE, the fossil belonged to a young raptor-like dinosaur that lived in an ancient Alaskan habitat marked by harsh seasonal shifts and long, dark winters. That dinosaurs were nesting and hatching babies in these habitats indicates that they were capable of surviving the harsh winters, even when it snowed.

Source: www.smithsonianmag.com/