Ammonoidea

Ammonoids are an extinct group of marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish) than they are to shelled nautiloids such as the living Nautilus species. The earliest ammonites appear during the Devonian, and the last species died out during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

Ammonites are excellent index fossils, and it is often possible to link the rock layer in which a particular species or genus is found to specific geologic time periods. Their fossil shells usually take the form of planispirals, although there were some helically spiraled and nonspiraled forms (known as heteromorphs).

The name “ammonite”, from which the scientific term is derived, was inspired by the spiral shape of their fossilized shells, which somewhat resemble tightly coiled rams’ horns. Pliny the Elder (d. 79 AD near Pompeii) called fossils of these animals ammonis cornua (“horns of Ammon”) because the Egyptian god Ammon (Amun) was typically depicted wearing ram’s horns. Often the name of an ammonite genus ends in –ceras, which is Greek (κέρας) for “horn”.

Ammonites (subclass Ammonoidea) can be distinguished by their septa, the dividing walls that separate the chambers in the phragmocone, by the nature of their sutures where the septa joint the outer shell wall, and in general by their siphuncles.

Septa

Ammonoid septa characteristically have bulges and indentations and are to varying degrees convex from the front, distinguishing them from nautiloid septa which are typically simple concave dish-shaped structures. The topology of the septa, especially around the rim, results in the various suture patterns found.

Suture patterns

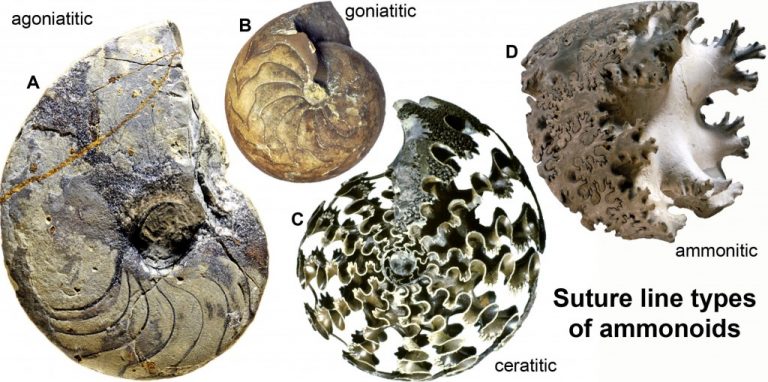

Three major types of suture patterns are found in the Ammonoidea:

- Goniatitic – numerous undivided lobes and saddles; typically 8 lobes around the conch. This pattern is characteristic of the Paleozoic ammonoids.

- Ceratitic – lobes have subdivided tips, giving them a saw-toothed appearance, and rounded undivided saddles. This suture pattern is characteristic of Triassic ammonoids and appears again in the Cretaceous “pseudoceratites”.

- Ammonitic – lobes and saddles are much subdivided (fluted); subdivisions are usually rounded instead of saw-toothed. Ammonoids of this type are the most important species from a biostratigraphical point of view. This suture type is characteristic of Jurassic and Cretaceous ammonoids, but extends back all the way to the Permian.

Siphuncle

The siphuncle in most ammonoids by far is a narrow tubular structure that runs along the outer rim, known as the venter, connecting the chambers of the phragmocone to the body or living chamber. This distinguishes them from living nautiloides (Nautilus and Allonautilus) and typical Nautilida. However, the very earliest nautiloids from the Late Cambrian and Ordovician typically had ventral siphuncles, although often proportionally larger than those in ammonites and more internally structured. The word “siphuncle” comes from the New Latin siphunculus, meaning “little siphon”.

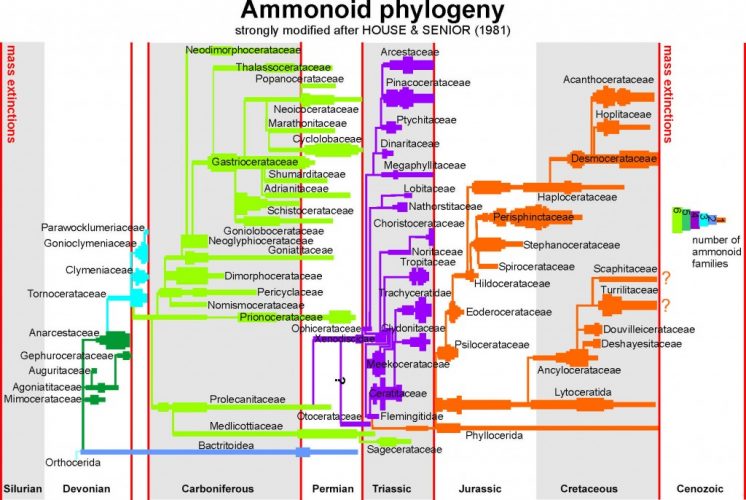

Originating from within the bactritoid nautiloids, the ammonoid cephalopods first appeared in the Devonian (circa 400 million years ago) and became extinct at the close of the Cretaceous (66 Mya) along with the dinosaurs. The classification of ammonoids is based in part on the ornamentation and structure of the septa comprising their shells’ gas chambers; by these and other characteristics we can divide subclass Ammonoidea into three orders and eight known suborders. While nearly all nautiloids show gently curving sutures, the ammonoid suture line (the intersection of the septum with the outer shell) is variably folded, forming saddles (or peaks) and lobes (or valleys).

Orders and suborders

The Ammonoidea can be divided into eight orders, listed here starting with the most primitive and going to the more derived:

- Anarcestida, Devonian

- Clymeniida, Upper Devonian

- Goniatitida, Middle Devonian – Upper Permian

- Prolecanitida, Upper Devonian – Upper Triassic

- Ceratitida, Permian – Triassic

- Phylloceratida, Triassic – Cretaceous

- Lytoceratida, Jurassic – Cretaceous

- Ammonitida, Lower Jurassic – Upper Cretaceous

In some classifications, these are left as suborders, included in only three orders: Goniatitida, Ceratitida, and Ammonitida.

Taxonomy of the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology

The Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology (Part L, 1957) divides the Ammonoidea, regarded simply as an order, into eight suborders, the Anarcestina, Clymeniina, Goniatitina, and Prolecanitina from the Paleozoic; the Ceratitina from the Triassic; and the Ammonitina, Lytoceratina, and Phylloceratina from the Jurassic and Cretaceous. In subsequent taxonomies, these are sometimes regarded as orders within the subclass Ammonoidea.

Extinction

The extinction of the ammonites, along with other marine animals and non-avian dinosaurs, has been attributed to the K-Pg extinction event, marking the end of the Cretaceous Period.

Eight or so species from only two families made it almost to the end of the Cretaceous, the order having gone through a more or less steady decline since the middle of the period. Six other families made it well into the upper Maastrichtian (uppermost stage of the Cretaceous), but were extinct well before the end. All told, 11 families entered the Maastrichtian, a decline from the 19 families known from the Cenomanian in the middle of the Cretaceous.

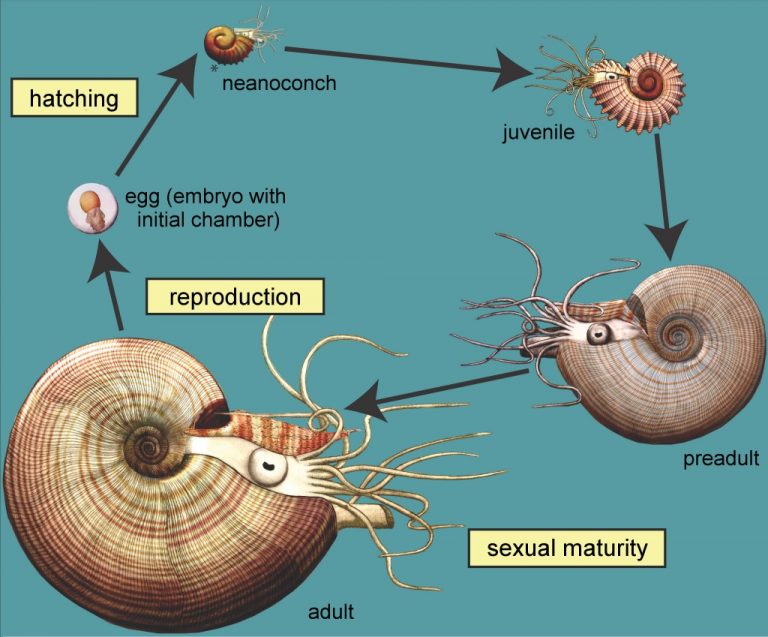

One reason given for their demise is the Cretaceous ammonites, being closely related to coleoids, had a similar reproductive strategy in which huge numbers of eggs were laid in a single batch at the end of the lifespan. These, along with juvenile ammonites, are thought to have been part of the plankton at the surface of the ocean, where they were killed off by the effects of an impact. Nautiloids, exemplified by modern nautiluses, are conversely thought to have had a reproductive strategy in which eggs were laid in smaller batches many times during the lifespan, and on the sea floor well away from any direct effects of such a bolide strike, and thus survived.

Many ammonite species were filter-feeders, so they might have been particularly susceptible to marine faunal turnovers and climatic change.