STUDY: Sharks, humans shared common ancestor 440 million years ago

"These different experiments in shark-like conditions give a picture of inevitability of the evolution of modern sharks," researcher Michael Coates said.

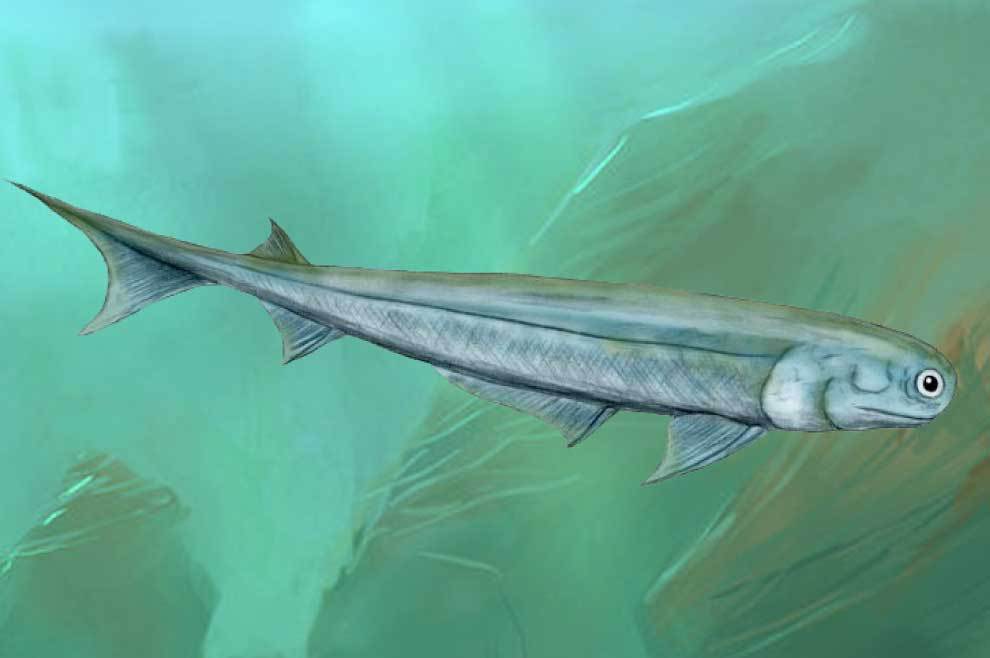

A basking shark-like fish -- only the size of a sardine -- is helping paleontologists better understand the earliest branches of the vertebrate family tree. The fish's 385 million-year-old remains suggest sharks and humans shared a common ancestor 440 million years ago.

The shark, named Gladbachus adentatus, was first discovered in Germany in 2001. But it wasn't until recently that, with the help of modern technology, scientists began to understand what they were looking at.

The specimen was found flattened and preserved in resin. The shark's exoskeleton, including its cranium, cartilage and gill details, were all neatly preserved, but its compressed state made it difficult to decipher what exactly the shark looked like.

Improved CT scanning technologies helped researchers recreate the shark in 3D.

"Gladbachus was not your typical shark," Katharine Criswell, a zoologist and research fellow at the University of Cambridge, told UPI. "It was almost a meter long and had a large and broad head with very tiny teeth, suggesting it was a suspension feeder similar to modern basking sharks."

Criswell and her colleagues were drawn to Gladbachus because of the potential insights it offered -- insights into a period of shark evolution of which little is understood.

Gladbachus lived during the Devonian period, between 416 million to 358 million years ago.

"We know of only a handful of completely preserved early shark fossils from this time period, and Gladbachus is one of the oldest," Criswell said.

The lack of shark remains from the period has long puzzled scientists.

"Sharks are thought of as a very conservative, primitive group and one of the best available early primitive models for vertebrates as a whole," said Michael Coates, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Chicago. "But they also present a paradox."

The fossil evidence -- or lack there of -- doesn't support the conception of sharks as a slowly evolving, primitive group.

"Bony fishes goes back deep into the fossil record, as far back 420 million years," Coates said. "There is a better record of bony fishes than there is of anything shark-like."

The vertebrate lineage that began with bony fishes eventually spawned mammals, including humans. Sharks, which utilize more cartilage than bone, split off and formed a separate branch. But with few fossils of early sharks or shark-like fish, scientists have struggled to pinpoint the split.

Thanks to Gladbachus, scientists are starting to nail down the timing of early vertebrate evolution.

Even if the shark offers some clarity, evolution is never straightforward. The transition from primitive shark-like fish to advanced or specialized shark species wasn't smooth.

Coates likens early species like Gladbachus to an evolutionary experiment. Other shark-like species represent separate but similar experiments, each trying out a variety of evolutionary adaptations.

"These different experiments in shark-like conditions give a picture of inevitability of the evolution of modern sharks," Coates said.

But a species isn't just a single experiment. Each species -- each specimen, even -- is a thousand different anatomical experiments at once. Some of those experiments prove successful enough that they become standard.

By better understanding the relationship between early sharks and bony fish, scientists can trace the origins of anatomical structures shared by all vertebrates.

"The body plan of jawed vertebrates, the group that includes humans, fish with bony skeletons, and sharks, is distinguished by features like jaws, teeth, and two sets of paired fins," Criswell said. "This body plan can be traced back to the evolutionary origin of sharks and bony fishes."

By comparing the anatomical makeup of Gladbachus with data from other early shark and fish fossils, researchers showed the first jawed vertebrates emerged nearly 10 million years earlier than was previously thought. They detailed the revelation in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Researchers believe remains of more shark-like and bony fish experiments are out there waiting to be discovered.

"Each one will help us calibrate the timescale of our shared evolutionary traits," Coates said.

Source: www.upi.com