Ankylorhiza tiedemani: Large Dolphin from Oligocene Epoch was Fast-Swimming Apex Predator

Paleontologists have found and described the first nearly complete skeleton of Ankylorhiza tiedemani, an extinct large dolphin that lived about 24 million years ago (Oligocene Epoch).

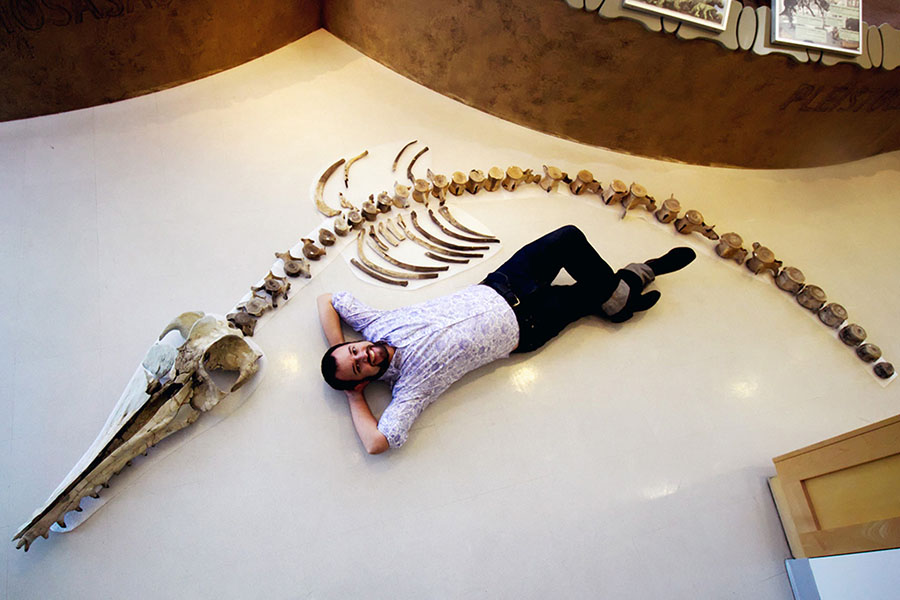

With a body length of 4.8 m (15.7 feet), Ankylorhiza tiedemani was the largest member of the group Odontoceti (toothed whales) during the Oligocene — a size not surpassed until the early Miocene by sperm whales.

The extinct animal was first described in the 1800s from a large fragmentary skull. Its first skeleton was discovered in the 1970s by then Charleston Museum Natural History curator Albert Sanders.

The nearly complete skeleton analyzed in the new study was found in the 1990s in South Carolina by commercial paleontologist Mark Havenstein. It was later acquired by private fossil collector Mace Brown and subsequently donated to the Mace Brown Museum of Natural History at the College of Charleston.

The specimen includes a well-preserved skull, most of the vertebral column, ribcage and one flipper.

“The discovery is important because it is one of the first skeletons found of a very early member of the toothed whales (dolphins, porpoises, and sperm whales), shortly after they diverged around 35-36 million years ago from baleen whales,” said Dr. Robert Boessenecker, a paleontologist in the Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences at the College of Charleston.

“What makes that important is its evolutionary position as a very early branching dolphin.”

“Most early dolphins are known only from skulls, so having a skeleton with flippers and most of the vertebrae gives us an unprecedented look into the evolution of swimming adaptations.”

“That unprecedented window surprisingly told us that baleen whales and dolphins have many similarities owing to convergent evolution since their evolutionary split 35 million years ago.”

The skeleton of Ankylorhiza tiedemani shows a few adaptations for faster swimming than other smaller dolphins, but also shows several primitive features.

“These primitive features are surprising because paleontologists and biologists long assumed that many of the adaptations for rapid swimming in baleen whales and toothed whales were ancient adaptations shared thanks to their common heritage over the past 35 million years,” Dr. Boessenecker said.

“The degree to which baleen whales and dolphins independently arrive at the same overall swimming adaptations, rather than these traits evolving once in the common ancestor of both groups, surprised us,” he added.

“Some examples include the narrowing of the tail stock, increase in the number of tail vertebrae, and shortening of the humerus (upper arm bone) in the flipper.”

“This is not apparent in different lineages of seals and sea lions, for example, which evolved into different modes of swimming and have very different looking postcranial skeletons.”

“It’s as if the addition of extra finger bones in the flipper and the locking of the elbow joint has forced both major groups of cetaceans down a similar evolutionary pathway in terms of locomotion.”

Multiple lines of evidence show that Ankylorhiza tiedemani was a top predator in the community in which it lived.

The species was very clearly preying upon large-bodied prey like a killer whale, and is the first echolocating whale to become an apex predator.

When Ankylorhiza tiedemani became extinct by about 23 million years ago, killer sperm whales and the shark-toothed dolphin Squalodon evolved and reoccupied the niche within 5 million years.

After the last killer sperm whales died out about 5 million years ago, the niche was left open until the ice ages, with the evolution of killer whales about 1 or 2 million years ago.

“Whales and dolphins have a complicated and long evolutionary history, and at a glance, you may not get that impression from modern species,” Dr. Boessenecker said.

“The fossil record has really cracked open this long, winding evolutionary path, and fossils like Ankylorhiza tiedemani help illuminate how this happened.”

The findings were published in the journal Current Biology.

_____

Robert W. Boessenecker et al. Convergent Evolution of Swimming Adaptations in Modern Whales Revealed by a Large Macrophagous Dolphin from the Oligocene of South Carolina. Current Biology, published online July 9, 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.012

Source: www.sci-news.com/