Paleontologists Find Massive Marine Reptile in Stomach of Triassic Ichthyosaur

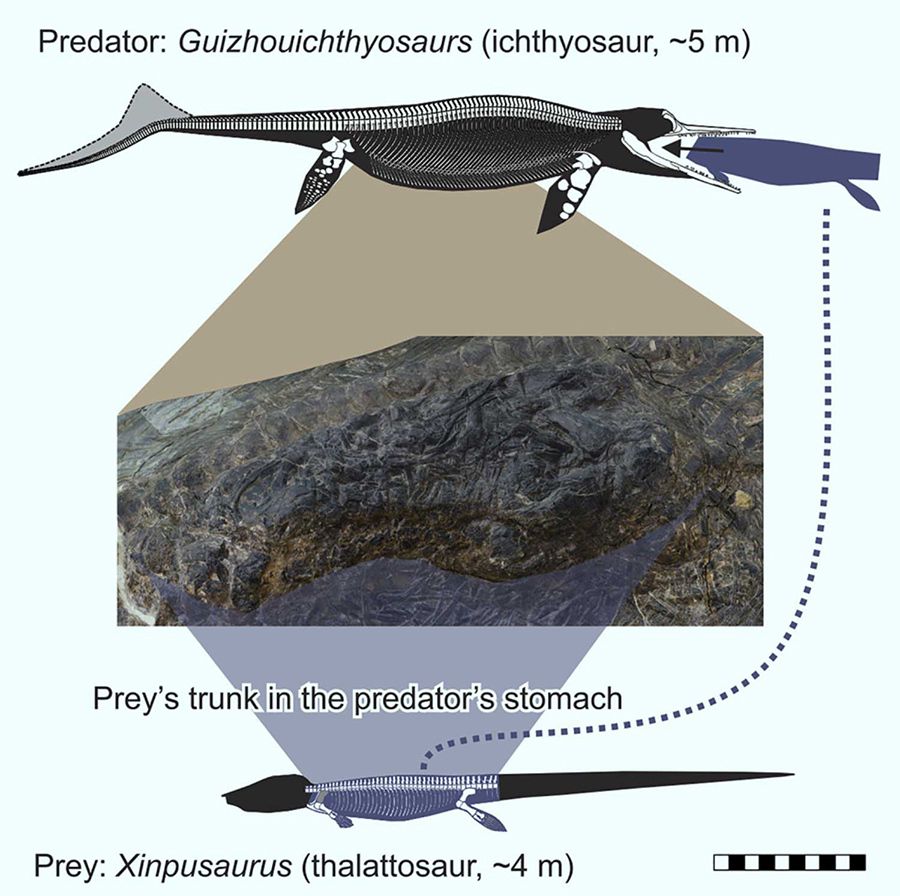

A new fossil of Guizhouichthyosaurus, a 5-m- (16.4-foot) long ichthyosaur that swam in Middle Triassic oceans some 240 million years ago, contains the remains of the 4-m- (13.1-foot) long thalattosaur Xinpusaurus xingyiensis, according to new research led by paleontologists from the University of California, Davis and Peking University. The work could be the oldest direct evidence that Triassic marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs — previously thought to be cephalopod feeders — were apex megapredators.

The ichthyosaurs were a group of marine reptiles that appeared in the oceans after the Permian mass extinction, about 250 million years ago.

They had fish-like bodies similar to modern tuna, but breathed air like dolphins and whales.

Like modern orca or great white sharks, they may have been apex predators of their ecosystems, but until recently there has been little direct evidence of this.

The new specimen of the ichthyosaur Guizhouichthyosaurus was discovered in Guizhou province, China, in 2010.

“We have never found articulated remains of a large reptile in the stomach of gigantic predators from the age of dinosaurs, such as marine reptiles and dinosaurs,” said University of California, Davis Professor Ryosuke Motani, co-lead author of the study.

“We always guessed from tooth shape and jaw design that these predators must have fed on large prey but now we have direct evidence that they did.”

Guizhouichthyosaurus was almost 5 m long, while its prey was about 4 m long, although thalattosaurs had skinnier bodies than ichythyosaurs.

The new specimen represents the oldest direct record of megafaunal predation by marine tetrapods and also sets the record for the largest prey size of Mesozoic marine reptiles at 4 m, which is larger than the previous record of 2.5 m (8.2 feet).

“Our ichthyosaur’s stomach contents weren’t etched by stomach acid, so it must have died quite soon after ingesting this food item,” Professor Motani said.

“At first, we just didn’t believe it, but after spending several years visiting the dig site and looking at the same specimens, we finally were able to swallow what we were seeing.”

“We now have a really solid articulated fossil in the stomach of a marine reptile for the first time,” he added.

“Before, we guessed that they must have eaten these big things, but now, we can say for sure that they did eat large animals.”

“This also suggests that megapredation was probably more common than we previously thought.”

Guizhouichthyosaurus’ last meal appears to be the middle section of Xinpusaurus xingyiensis, from its front to back limbs.

The predator has grasping teeth yet swallowed the body trunk in one to several pieces.

“Predators that feed on large animals are often assumed to have large teeth adapted for slicing up prey,” the paleontologists said.

“Guizhouichthyosaurus had relatively small, peg-like teeth, which were thought to be adapted for grasping soft prey such as the squid-like animals abundant in the oceans at the time.”

Interestingly, a fossil of what appears to be the tail section of Xinpusaurus xingyiensis was found nearby.

“It’s clear that you don’t need slicing teeth to be a megapredator,” Professor Motani said.

“Guizhouichthyosaurus probably used its teeth to grip the prey, perhaps breaking the spine with the force of its bite, then ripped or tore the prey apart.”

“Modern apex predators such as orca, leopard seals and crocodiles use a similar strategy.”

While the scientists now know that Guizhouichthyosaurus could eat animals as large as the thalattosaur, they don’t know if it killed this individual, or simply scavenged it.

“Nobody was there filming it,” Professor Motani said.

“However, there is reason to believe this was not a case of scavenging: modern marine decomposition studies suggest that if left to decay, the thalattosaur’s limbs would disintegrate and detach before the tail. Instead, we found the opposite in these fossils.”

The team’s paper was published in the journal iScience.

_____

Da-Yong Jiang et al. Evidence Supporting Predation of 4-m Marine Reptile by Triassic Megapredator. iScience, published online August 20, 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101347

Source: www.sci-news.com/