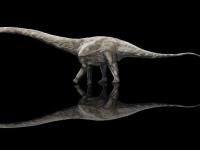

Siats: The Giant before the Tyrant!

Tyrannosaurs weren’t the only big carnivores to tromp through the Mesozoic of North America. Before the tyrant lizards were huge, there was another giant terrorizing the American West: Siats! Named for a Ute mythological giant, Siats was a bus-sized carnivore in the middle of the Cretaceous of Utah (99 million years ago). The giant had close relatives – the neovenatorids – on almost all the continents. This is a bit of a mystery because the continents were getting spread out by 99 million years, making it tough to explain how the neovenatorids conquered the world. In North America, this global dynasty replaced another family of giants: the carcharodontosaurids which included Acrocanthosaurus the top carnivore of the Early Cretaceous of Western and Eastern North America. The discovery of Siats shows two things: 1) different lineages of carnivorous dinosaurs could get really big and 2) T. rex is just the last monarch to fill the giant carnivore niche in North America. It’s a toothy, terrifying tale on Past Time!

Past Time Prequel: The Dy-nasties before the Tyrants!

Most people know who Tyrannosaurus rex was: a carnivorous giant from North America who closed the Age of the Dinosaurs 65 million years ago. But T. rex wasn’t the only giant to stomp through the North American continent.

Lythronax lived 80 million years ago and started the tyrannosaur dynasty that lasted until the end of the Mesozoic (Age of Dinosaurs). But that doesn’t mean North America was a quiet, safe place until Lythronax showed up. Instead, Lythronax and the rest of the tyrannosaurs were filling in a large-bodied carnivore niche that had been filled by many different species of giants that were not closely related to tyrannosaurs.

All meat-eating dinosaurs belong to a large group called the Theropoda. The theropod lineage was really diverse, ranging from the large toothy giants like Majungasaurus and Tyrannosaurus, to bizarre, toothless bipeds like Oviraptor and Gallimimus, on down to small feather friends like hummingbirds and Velociraptor.

Within the group Theropoda there were a lot of experiments in becoming giant carnivores. One of most iconic North American dinosaurs to reach monstrous proportions was Allosaurus (meaning “Other Lizard”…not the most creative name ever concocted). Allosaurus stomped through the Jurassic of North America about 150 million years ago and is well-known from plenty of fossils found in the American West where she is often shown stalking the giant sauropods that shared the environment with the giant carnivore. At first glance, Allosaurus might look like a lighter version of T. rex, but details of her anatomy show her lineage was distinct from the tyrannosaurs.

After Allosaurus went extinct, the large-bodied carnivore niche was filled in during the Early Cretaceous ( about 110 million years ago) by Acrocathosaurus. Acrocanthosaurus had a distinctive profile with an almost sail-like ridge running down her back. Fossils of Acrocanthosaurus have been found in the North American West from Early Cretaceous deposits, but this animal is also near-and-dear to Adam’s heart because some large theropod fossils found on the East Coast of North America in Maryland may have belonged to Acrocanthosaurus.

Acrocanthosaurus and its closest relatives are called the carcharodontosaurids (meaning “Great white shark-toothed lizards) and they are distinct from the Allosaurus lineage that and distinct from the lineage that would lead to Lythronax and T. rex. The carcharadontosaurids, such as Acrocathosaurus, dominated the large carnivore niche for millions of years.

But then there was a gap in the fossil record during the middle Cretaceous where there didn’t seem to be any large carnivores until a giant was discovered in Utah…

Paleontologists from the Field Museum in Chicago, including Dr. Lindsay Zanno and Dr. Peter Makovicky, announced the discovery of Siats (pronounced “See-atch”) on November 22, 2013 in the scientific journal Nature Communications. As experts in theropod evolution, Dr. Zanno and Dr. Makovicky knew by looking at the pieces of the skeleton they had recovered from 99 million year old rocks in Utah that they had a new genus and species of dinosaur and it didn’t belong to the group that includes Allosaurus, OR the group Carcharodontosauridae that includes Acrocanthosaurus, OR the tyrannosaurs.

Instead, Siats belonged to a whole different lineage called the Neovenatoridae (meaning “New hunters”). There are a lot of names to juggle here, but that’s part of the point. There were all these different groups of dinosaurs converging on the same massive, meat-eating body plan over and over again, telling paleontologists that there was some kind of evolutionary advantage selected for being big in each of these groups. Tyrannosaurus was not a monstrous outlier in North American dinosaur evolution, but the final successor to a long-occupied giant carnivore niche.

Siats is a giant from Ute Indian mythology who would snatch up small children who wandered too far from camp at night. Ninety-nine million years ago, the earliest relatives of Lythronax and Tyrannosaurus were small-bodied theropods that would have reminded you of Velociraptor more than the giant tyrants they would become. One of these is illustrated in the body size diagram in this post. They probably would have seen Siats as a terrifying monster waiting to snatch them up, too!

Siats’s family, the neovenatorids, were not a quiet off-shoot in dinosaur evolution, filling in the gaps left by the carcarodontisaurids, but a global dynasty. Species belonging to the Neovenatoridae have been found all over the world including Eurasia, South America, Africa, and Australia. Carcharodontosaurids covered a lot of ground, as you can see in the map, but they didn’t have the global reach of the neovenatorids, including Siats.

With the discovery of Siats the history of theropod diversity, neovenatorid biogeography, and North American carnivores becomes even more complicated and even more interesting! Each new fossil discovery fills in another gap in the fossil record making it possible to understand the relationships between continents and ecosystems across vast amounts of time and space, telling paleontologists about past ecosystems so we can better understand the present!

Source: www.NatGeo.com