Diceratops hatcheri: The Mystery Dinosaur Being Kept in the Museum Basement

When the new fossil hall at the National Museum of Natural History in the US opens next June, it will show off hundreds of the Smithsonian's finest prehistoric specimens, including the newly acquired star of the Late Cretaceous show, "The Nation's T. rex".

But just a tiny sliver of the museum's 40 million fossils will be on display.

"You're covering three-plus billion years of life history, and there's only so much you can pack in there," said Hans-Dieter Sues, chairman of the museum's paleontology department.

Here's the story of a mysterious dinosaur that didn't make the cut.

First, a few details: It's not a whole dinosaur, just a six-foot-long (182 cms) skull. The rest of its body parts were probably carried off by ancient scavengers or swept away by the elements during the 66-68 million years between its death and its discovery in Niobrara County, Wyoming, in 1891.

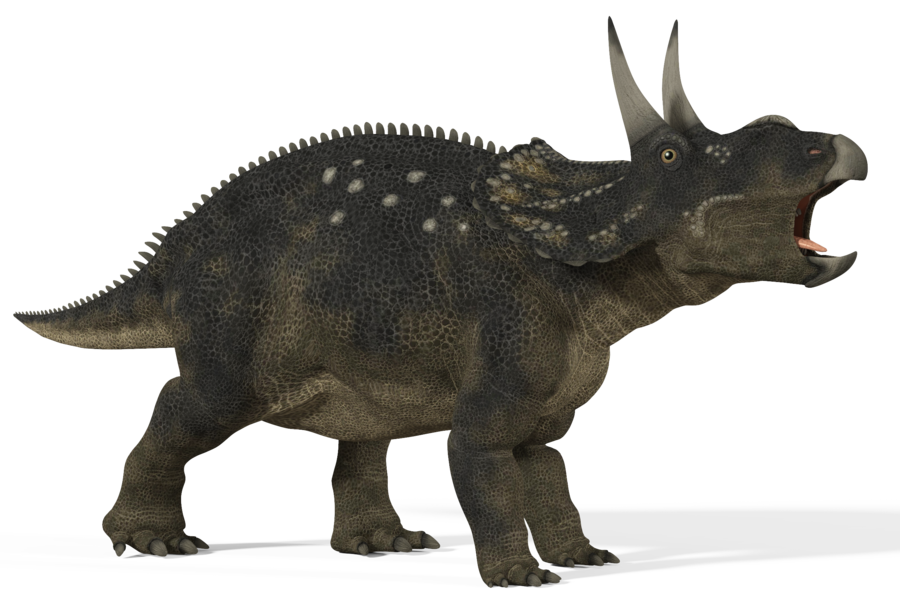

It ate plants, had two horns over its eyes and looked mostly like a Triceratops, except for a smooth rise on its snout where the third horn would've been.

It has three names - four if you count the museum's catalogue number, USNM 2412 - yet paleontologists are not entirely sure what to call it.

In 1905, it was named Diceratops hatcheri. "Diceratops" means two-horned face; "hatcheri" is a nod to John Bell Hatcher, the famed fossil hunter who discovered it. It went by that name for over a century.

In 2007, however, a Russian author noticed that the name Diceratops already had been given to an insect in 1868. Two animals can't share the same name, so he renamed the dinosaur Nedoceratops, a rather mean-spirited label that translates as "insufficient horned face".

A year later, a Portuguese palaeontologist who hadn't heard about the renaming proposed tweaking the original just a bit, to Diceratus. Some references now list all three monikers so people don't get confused.

All those names may be superfluous anyway, Sues said, because most paleontologists now believe the skull belonged not to a different species but to a common Triceratops that, through illness or genetic mutation, had a nose that just didn't look like the others.

"It is the Rudolph of the triceratops!" joked Sues, who nevertheless doesn't care for giving fossils cute nicknames and probably won't be thrilled that, for simplicity's sake, we're calling this one Rudolph for the rest of this story.

In addition to an oddly shaped nose, Rudolph's skull has a frill that is perforated by three asymmetrical holes. Sues thinks they may have been caused by the same pathology that stunted the animal's horn because they appear too smooth to have been caused by damage.

"The problem with dinosaurs is you often have so few specimens," Sues said, so you see few variations. "If you had them only in fossil form, you might have a problem seeing that the skull of a German shepherd and the skull of a French bulldog are the same species."

In 2009, two scientists caused a palaeontological hubbub when they hypothesised that Triceratops was actually a juvenile Torosaurus, a 30-foot-long, six-tonne horned plant-eater, and that Rudolph may have been an adolescent link between the two. (Other scientists strongly disagreed.)

It is not merely Rudolph's lineage that is intriguing, Sues said, but also its discovery, or rather its discoverer.

Hatcher was a colourful fossil hunter who first worked for Othniel Charles Marsh, the first professor of paleontology at Yale. (Marsh's increasingly malicious rivalry with Philadelphia palaeontologist Edward Drinker Cope became known as the "Bone Wars". This was a huge story line in its day, when palaeontology was a relatively new science, and the most spectacular finds were coming out of what was literally the Wild West.)

Hatcher discovered many important dinosaur fossils, including Torosaurus. He was also known for his poker-player prowess, Sues said, and once had to rely on his six-shooters to help him escape a town in Argentina after a card game left some locals broke and angry.

According to Hatcher's description in the 1907 reference work The Ceratopsia, he found Rudolph protruding from sandstone, nose-down and without a lower jaw, in the same general rock formation where he had found Torosaurus and many Triceratops.

Hatcher sent his fossil finds, including Rudolph, back east to Marsh's growing collection at Yale. After Marsh's death in 1899, the skull came to the Smithsonian among five train cars full of fossils that became the foundation of the museum's dinosaur collection.

Sues said we should not feel sorry for Rudolph the Flat-Nosed Triceratops, which grew to be a very large adult in a dino-eat-dino world.

And although its skull will rest among the trove of fossils in the basement of the museum rather than in the slick new fossil hall upstairs, it may have been dealt a better hand than the normal-horned Triceratops that will represent the species to the public. That one, Hatcher, has been posed lying on the ground, about to have its frill ripped off by the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex.

- The Washington Post

Source: www.stuff.co.nz