Jurassic Park And The Dinosaur Explosion, Or Why Your Kids Know More About Dinos Than You

Wanna feel dumb? Try reading a book about dinosaurs with a kid.

This happened to me.

My three-year-old, Finn, is going through a bit of a dinosaur phase. Our apartment looks more like a deleted scene from Jurassic Park than a photo shoot for Vogue Living.

From pyjamas to t-shirts and hoodies (just quietly I'm super jealous of the T. rex hoodie), to night lights, stickers and those iconic plastic figurines, dinosaurs still roam the land at our place.

Oh yeah ... and the books. So. Many. Dinosaur. Books.

I don't know the last time you read a book about dinosaurs, but if you grew up in the 90s (or earlier) you might be in for a bit of a shock when you do.

While Finn and his friends can name pretty much all the dinosaurs in these books ... I can't.

There are so many dinosaurs I just don't recognise. Sinosauropteryx? Gordodon? Giganotosaurus? Eoraptor? Really?

Back in my day, we had old favourites like Tyrannosaurus rex, Stegosaurus, Triceratops, and Brontosaurus, and that was about it. And, like Finn, I was dino-obsessed as a kid. So what's going on?

Well it turns out I'm not alone. Like me, palaeontologist Steve Brusatte of the University of Edinburgh grew up during the late 80s/early 90s.

"The image of dinosaurs in those books I read as a kid? That image is extinct," Dr Brusatte says.

So why does my three-year-old know so much more about dinosaurs than I ever did?

The golden age of dinosaur discovery is now

In the past few decades there's been an explosion of dinosaur discoveries, Dr Brusatte says.

"It really is a golden age. People are finding more species of dinosaur than ever before."

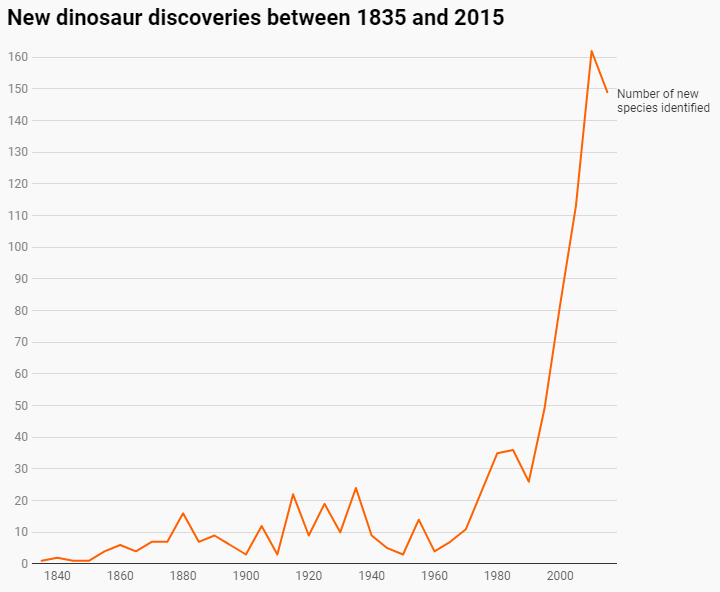

Palaeontologist Jon Tennant's research shows just how dramatic the recent rise in discoveries has been.

Dr Tennant was originally trawling through the Paleobiology database — an electronic record of every fossil documented via publication in an academic journal — looking for evidence of dinosaur extinction events other than the one that wiped non-avian dinosaurs off the planet.

"I was just sort of playing around one day when I decided to see what would happen if we looked at it from a slightly different angle," he recalls.

Instead of considering dinosaur fossils relative to dinosaur history — when in time and where these dinosaurs lived — Dr Tennant began to analyse the discovery of these fossils relative to our own human history.

The records revealed a slow and incremental growth in new discoveries in the 100 years following the first flurry, known as the Great Dinosaur Rush or Bone Wars, in the 1880s.

"But then around the 1990s something strange happened, and we see this this huge explosive growth in the number of discoveries."

EMBED: Dinosaur discoveries by year

That sudden, exponential shift upwards is why I hadn't heard of an eoraptor before Finn pointed one out to me.

So what was driving the rapid and massive increase in the number of new dinosaur species?

No kidding, the 1993 smash hit movie Jurassic Park was a big deal for palaeontology.

"It was a little over 25 years ago that that film came out and that changed everything," Dr Brusatte says.

"It brought dinosaurs into pop culture in a way they had never been before."

In turn, the surge in public interest drove a resurgence in palaeontology, Dr Tennant adds.

"People actually used Jurassic Park as leverage to get funding to conduct more dinosaur research in North America because it had such a huge public sway."

But it wasn't just North America, the film's impact was felt worldwide.

"I have colleagues all over the world — the generation of palaeontologists in their 30s — that say Jurassic Park is what got them into dinosaurs," Dr Brusatte says.

And globalisation of palaeontology has driven the explosion of new discoveries.

For much of its life as a discipline, palaeontology was a thing of Europe and North America.

"That has remained embedded in our mind as what is normal," Dr Tennant explains.

"If you think about the most well-known or most loved dinosaurs it's things like T. rex or triceratops. These are animals that come from North America."

But over the past few decades, the hunt for dinosaurs has expanded all over the world.

"There are people in China, in Brazil, in Argentina, in these enormous developing countries that are full of wide, open spaces, full of rocks bursting with dinosaur bones," Dr Brusatte says.

And it's not just that more people in more places are finding more fossils; it's also the type of fossils they're finding.

"Beautiful chocolate brown bones sticking out from this tan coloured limestone," recalls Dr Brusatte, pondering his role in the discovery of the Zhenyuanlong suni fossil in China.

"Sharp teeth, sharp claws, looks so much like velociraptor, but covered in feathers. Feathers on the tail, feathers on the body, feathers on the head, feathers on the arms; actual quill feathers forming wings.

"And that drives it home — a fossil like this, that's over 100 million years old, conveys this powerful message that birds evolved from dinosaurs."

The fossils being discovered in new territories — in particular China, and Mongolia — have completely changed how we think about dinosaurs (and birds for that matter).

These feathered fossils have created a kind of gold rush effect as everyone races to find the next new species. This in turn amplifies the rate of new discoveries, pushing the line on Dr Tennant's graph ever steeper.

A lot of these new discoveries are made not by palaeontologists, but by ordinary people.

"We can't be out in the field for six months a year on expeditions like we're Indiana Jones" Dr Brusatte explains.

"We do find our own fossils of course, but so many of these new discoveries are made not by scientists, but by all sorts of people; farmers, construction workers, hikers, sometimes kids out hiking with their parents.

"And that's an amazing thing. Palaeontology, at least the discovery side of palaeontology, is open to everybody."

The dark side of the golden age

But palaeontology's inherent accessibility creates its own problems.

"Poaching is an issue in palaeontology," Dr Brusatte says. "Particularly in certain parts of the world. It's a big issue in Mongolia. And it's also an issue in parts of China."

The black market fossil trade continues to drive fossil poaching. And money often trumps the law.

"There are wealthy folks out there who want to have a T. rex in their living room," explains Dr Brusatte.

"Who doesn't want to have a T. rex in their living room, right?

"But it means that there is a bit of a market for this.

"It's similar in some ways to the art market. Some of these amazing fossils are unique pieces that high-end collectors really want. And that breeds a black market."

Dr Brusatte doesn't pull punches when it comes to fossil poaching.

"Simply put, it's wrong because it's against the law," he says. "I'm not saying people can't go out and find fossils, or that you have to be a scientist or academic. What I am saying is, no matter who you are, you've got to follow the law."

Trading in black market fossils also creates problems for researchers and academics as the legitimacy of fossils held in private collections is brought into question.

Peer review is the backbone of modern science. And the concern among some palaeontologists is that fossil specimens held in private collections threaten to undermine the scientific method.

"Most journals these days say if you want to publish on a new specimen, the data — in this case a dinosaur fossil — has to be publicly accessible," Dr Tennant says.

While private fossils might be available to some researchers, there's no guarantee they'll be available in perpetuity to any researchers who want to study them.

"As scientists we have to do repeatable work," Dr Brusatte explains.

"And it's impossible to do proper scrupulous science on a fossil that's not guaranteed to be available to other scientists."

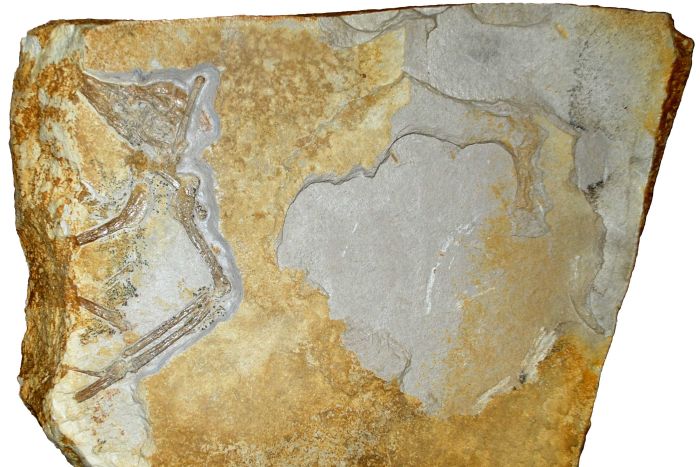

The controversy around a recent paper describing a fossil of a new species of archaeopteryx is a case in point. The fossil, dubbed 'The Phantom' was discovered in the early 1990s in Germany.

Palaeontologists caught a glimpse of a cast of The Phantom in 1996, but it was hidden from view again until after it was sold in 2009 to palaeontologist Raimund Albersdorfer, who made it available in 2011.

"The specimen was housed within a private collection," Dr Tennant explains.

"A lot of people were like, 'You can't publish this because it's a private specimen!' And then people were like, 'Would you rather not know about this or know a little bit but not have access to it?'"

Not everything needs to be in the public domain, but access to rare specimens is critical, Dr Brusatte says.

"Like so many palaeontologists I got my start collecting fossils as a teenager collecting brachiopods, these little shelled creatures," he recalls.

"If we take that away from people, we're taking away the magic of science and discovery. That would be a ridiculous overstep.

"But if a unique, scientifically important fossil disappears into the living room of some wealthy business person never to be seen again, never to be studied, never to be enjoyed by the public, that breaks my heart."

Dr Albersdörfer has given the 'The Phantom' archaeopteryx fossil to a public collection in Munich on long-term loan and has committed not to sell it to a non-public entity.

Will the dino explosion ever end?

There's one final question to ask of this explosion in our dinosaur knowledge: when will it end? Or, indeed, will it end? Could Dr Tennant's graph just keep shooting skywards forever?

"At some point you'd like to think that we would discover every possible dinosaur that's buried in the ground. Right?" Dr Tennant says.

"But at the moment I don't know where that limit is.

"Even in places where people have been discovering dinosaurs for 100 or 150 years, there are still new discoveries all the time."

Dr Brusatte agrees.

"Don't worry, we're not running out of dinosaurs. We are still finding new dinosaurs all over the place," he says.

"Even if we stopped finding dinosaur fossils today — which is not going to happen — there's going be new techniques, new technologies, new types of experiments, instruments and ways of thinking that will help us study dinosaurs we already have in ways we never would have thought possible before."

So, if Finn has children one day, will he be overwhelmed by how few dinosaurs he recognises, like I am?

"Twenty years from now we're going to look back at what we knew about dinosaurs at this moment in time," Dr Brusatte says.

"Things are [not] going to be completely revolutionised; it's not like everything we thought we knew in 2020 is going to be wrong.

"But there's probably going to be a bunch of new, weird groups of dinosaurs that we never could have anticipated. So who knows what's going to be found next."

Or who's going to find it — right Finn?

Source: www.abc.net.au